PERTH

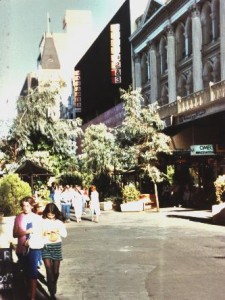

ACADEMY TWIN CINEMAS/ACADEMY WEST END ALTERNATIVE CINEMAS/ LUMIERE, Wellington St, Perth

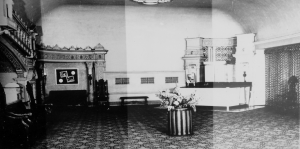

In the late seventies, TVW Enterprises, the company running the television channel TVW 7, built the huge Entertainment Centre on a large site on the north side of Wellington St near the Perth Railway Station. The complex (which contained a vast entertainment stadium, convention facilities and restaurants) was officially opened on 27 December 1974, and the two cinemas on its ground floor were opened on 17 January 1975. These were named the Academy Cinemas, One and Two, and were leased to City Theatres, which had been from February 1973 owned by a consortium of which TVW Enterprises was a major shareholder. In August 1978 TVW Enterprises bought out the other shareholders, leaving the management of the Academy Cinemas with those employed previously by the consortium.

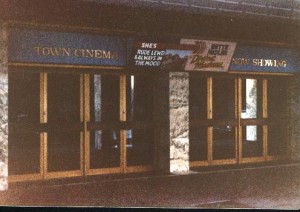

Three-D was shown briefly in 1985, then in June 1986 the cinemas became the Academy West End Alternative Cinemas, programming for the “film buff”, the kind of audience catered for by the Perth Film Festival and the Windsor (Nedlands) and New Oxford (Leederville). However, the arthouse policy survived only for a short time, and the cinemas closed 1 July 1988, after Hoyts took them over. They were then taken on in 1989 by James Woods and leased to the Film and Television Institute (WA), which had formerly screened only in Fremantle.

They renamed the venue the Lumiere. In 1993 it was listed as having 405 seats in Cinema 1 and 373 in Cinema 2, and to be presenting live performances as well as films. However, it closed on 28 June 1996, and the lease was not again taken up. In 2002, there were rumours of demolition, bitterly apposed by heritage lobbyists. In 2003, it was reported that ‘Multiplex (the company) has secured an option to buy the mothballed Entertainment Complex for $25 million. A $40 million redevelopment is proposed.’ (Kino no.86, p.42) Further reports suggest that any redevelopment will no longer accommodate cinema: ‘A $50 million redevelopment of the closed Perth Entertainment Centre has been proposed which will feature a retractable roof to allow the centre to compete for more tennis and other big events.’ (Kino, no.87, p.38)

Sources: Max D. Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, Sussex, 1986, p.73

Jack Honnibal, ´The theatres of Perth 1939 – 1993′, Kino, no.45, September 1993, p.29

Bob Parkinson, ´Field report’, Kino, no.41, September 1992, p.13

Kino, no.17, September 1986, p.24; no.25, September 1988, p.23; no.29, September 1989, p.23; no.31, March 1990, p.23 no.38, December 1991, p.27; no.45, September 1993, p.31; no.57, September 1996, p.31; no.62, Summer 1997, p.35; no.80, Winter 2002, p.54; no.81, Spring 2002, p.39; no.86, Summer 2003, p.42; no.87, Autumn 2004, p.38

West Australian, 27 December 1974, 1974 – 1997

Interview (Ina Bertrand): Arthur Stiles (1985)

Photos: 1 exterior, colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

1 exterior, 3 interiors, b&w, West Australian, 27 December 1974

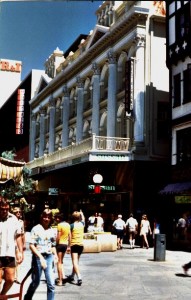

AMBASSADORS/HOYTS CINEMAS TWO AND THREE (AND FOUR)/HOYTS CENTRE, 629 Hay St, Perth

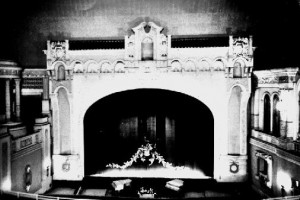

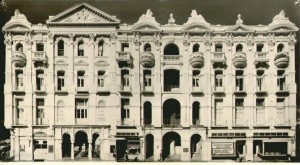

The programme of the opening night of the Ambassadors, on 29 September 1928, proclaimed:

There is but one Ambassadors. Never was a theatre so beautiful, or its glory so dearly bought but that it fades into insignificance beside this Florentine garden of music, of picture, of song which you see tonight for the first time.

This purple prose overlooked the fact that the Ambassadors was the third, and the smallest, of the atmospheric theatres built by Union Theatres in the state capitals of Australia in the twenties, the others being the Melbourne State and the Sydney Capitol. It was designed by Bohringer, Taylor and Johnson, who had also designed the Melbourne State.

Nevertheless, it was a first for Perth, and the theatre was able to compete successfully with Perth’s other great picture palaces of the decade – the Regent, the Capitol and the Prince of Wales. It was built under the guidance of Sir Thomas Coombe, the last thing he contributed to Union Theatres’ empire in Western Australia, before retiring.

To prepare those first-night patrons, the programme explained what an ´atmospheric’ theatre was, and what they might expect from this particular example:

Overhead in the sky you see stars twinkling in between the clouds that float, light as thistledown, across the heavens. It will be hard for you to believe that above them is a roof and that walls really surround you. For the ´atmospheric’ theatre, as its name implies, creates an atmosphere – an atmosphere where there is a very desirable feeling of intimacy and illusion to calm excited nerves, and prepare one and all to receive entertainment in ease and comfort. To secure this atmosphere, that you see here now, sculptors, painters, color artists and students of history, and many others, have been organised in Australian workshops.

Despite the appreciation shown to the local craftsmen who installed the interior, much stress was also placed on the widely scattered sources of the decorations themselves, from Paris, New York, Vienna, Berlin, Rome, Madrid, Chicago, Naples and London, among others. The exotic decor included stuffed pigeons and peacocks from Durban, South Africa, and reproductions of statuary from the great museums of Europe. Care was taken in the programme to point out the bona fides of these works of art, such as the Venus de Medici, ´signed by Cleomenes, son of Apollodorus, the Athenian, and …at present in the Uffizi Museum, Florence’: perhaps the patrons needed to be re-assured of the respectability of an environment in which they were surrounded by nude statues.

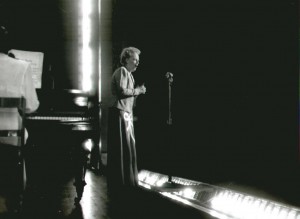

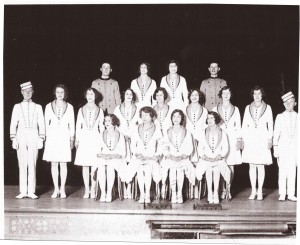

As well as the picture programme, the patrons could expect fine musical accompaniment, both from Bert Howell’s orchestra and from the Wurlitzer organ played on opening night by Les Waldron, in the glare of a spotlight as he rose on a stand from below the orchestra pit. The Ambassadors ballet, of eight local dancers under the direction of Estelle Anderson from the J.C.Williamson’s company, worked in conjunction with the orchestra to present prologues and other terpsichorean interludes.

Like most theatres in Perth, the Ambassadors claimed to be the coolest, and if the temperature was too unpleasant you could even walk up onto the roof and sit among the potted trees and shrubs of the Florentine Roof Garden. Much stress was also placed on the technical installations, both for the safety and comfort of patrons (lighting, ventilation, fire precautions) and for the quality and ease of viewing of the picture. A particular feature was the red velvet curtain, embossed with a peacock (now held by Ivan King).

Continuous pictures were no longer fashionable by 1928, though they continued at some of the cheaper venues like the Majestic and the Grand. Instead, the Ambassadors advertised four sessions daily. The doors opened at 10 a.m., with patrons entertained by the Wurlitzer till the 11 a.m. session, referred to as the ´early shopping session’. At 2.15 a session identical with the evening one commenced, then at 5 p.m. came a slightly shorter session ´for those remaining in town’. The main night session contained all the elements of the Unit entertainment – double feature films (or main feature and short features), with orchestral accompaniment, perhaps a stage prologue or interludes, and the Wurlitzer before the show and at interval.

The first sound films at the Ambassadors were on disc, opening about a year after sound had arrived in Perth. On one occasion, nearly 300ft of film was mangled in the projector and it was necessary to add exactly the right amount of replacement film, so that synchronisation with the disc was not lost. An ingenious solution was found. Instead of the piece of black film that was traditionally used, local film producer ´Dryblower’ Murphy was asked to make up the appropriate length of the words of the song that Colleen Moore was singing on the disc, and the audience never realised that it was meant to be any other way.

However, the theatre had sound-on-film equipment from the beginning as well, as they screened Movietone News. So it was comparatively simple to switch over to that system entirely when it became the accepted standard. The Ambassadors also maintained its orchestra and stage shows to accompany films longer than did other city theatre, and the mighty Wurlitzer remained a drawcard, even after the Ambassadors Orchestra was finally disbanded.

During 1931, when Union Theatres was in financial difficulties, a decision had to be made which of their two large showcase cinemas in the central city area would be closed – the Ambassadors or the Prince of Wales. The company opted to leave the Ambassadors open, despite it being the less profitable and the smaller of the two, because it contained four shops dependent on the income generated from cinema patrons and returning rents to the company, compared to only one shop associated with the Prince of Wales. So the Ambassadors joined the General Theatres group in 1932. Hamilton Brown, Union Theatres’ manager in Western Australia at the time, and noted for his entrepreneurial skills, tried very hard to rescue the ailing theatre. One gimmick was a wedding on stage before the opening of the film Lovers Courageous in July 1932. Live acts were also presented in support of the featured film on some occasions. But to continue to maintain a theatre as large as the Ambassadors, with nearly two thousand seats, was extremely difficult during the depression years.

Towards the end of the decade, Hoyts took over the theatre, and in 1938 it was remodelled, losing in the process much of the atmospherics which had contributed to its distinctive character:

Money has not been spared to make this theatre equal to the best in Perth. The entire front of the house has been modernised, the latest neon signs being incorporated on the facade of the building with charming simplicity, and the whole front, with its light treatment and modern lines, has a pleasing effect. Gone is the heavy, florid atmosphere of the old Ambassadors and in its place reigns a cheerful colour-scheme, combined with a maximum of comfort and restrained luxuriousness. The specially imported English carpet, upon which over 20 West Australian workers have been employed in sewing, is of a graceful pattern with an harmonious blending of colour. Comfortable, modern seating has been installed throughout in a tasteful deep green, the seats incorporating the latest scientific improvements in armchair comfort. (West Australian, 22 December 1938)

These alterations had probably been stimulated by the competition from the other theatres recently built – Hoyts’ own Plaza in 1937 and the Grand Theatre Co’s Piccadilly in 1938. It was a period when modernity was expected, and the Ambassadors lost some of its unique quality as a result. The theatre continued to screen regularly, though with mixed success, until it closed on 2 February 1972. The building was immediately demolished and its furnishings dispersed by auction.

HOYTS CINEMAS TWO AND THREE (AND FOUR)

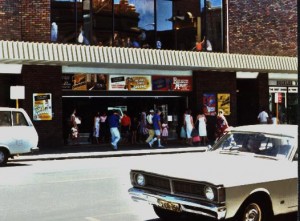

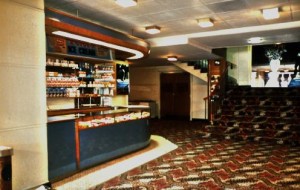

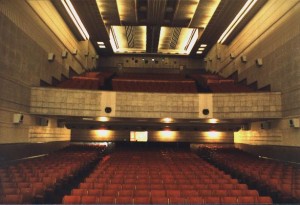

Three years later, the City Centre was built on the site, containing the Wanamba Arcade – a complex of shops and restaurants, including a theatre, known as Hoyts Cinema Two, with 859 seats:

Hoyts Cinema 2 will be one of Perth’s jazziest cinemas…

Be prepared for the decor – tri-striped and exciting, with wall hangings.

Former WA interior decorator Neville Marsh has chosen deep blue upholstery for the seats, blue carpeting and walls painted in blue, maroon and beige stripes….big ones!

Part of the carpet area is striped too…

Usherettes will wear long blue skirts and beige blouses.

The cinema also features unique spot-lighting.

Seating in Cinema 2 is comfortable. There is plenty of space between rows and the vinyl upholstery features tiny holes which allows the fabric to breathe. This keeps the seat cool.

The seats are also broad enough to give excellent shoulder support.

Cinema 2 has a 56ft screen.

The walls are acoustic – some even covered with felt.

(Daily News, 20 March, 1975)

This ultra-modern cinema opened on 20 March 1975, but even with only 859 seats it proved too big for the audiences of the late seventies. In 1978 it was divided down the middle, and re-opened 13 December as Hoyts Cinemas Two and Three, each seating 400. As well as new Philips projectors and Dolby sound system, the new theatres boasted historic photo-murals of Perth as it used to be, and pin-ball machines in the foyer.

In 1984 a third cinema (Cinema Four) was added to the complex, sharing the foyer and administration block with the other two cinemas. Cinema Four was built, however, like a Chinese box – inside the lounge of the old Theatre Royal, which had been next door to the Ambassadors in earlier days. An access door was knocked through the shared side wall, without interfering with the shops and offices now occupying the lower levels of the building.

HOYTS CENTRE

In 1988 Hoyts took over Cinema City, and after Hoyts Cinema One was closed the Cinema City theatres became Hoyts Cinema City (holding Hoyts Cinemas 1 – 4), and Hoyts Cinemas 2 – 4 (on the old Ambassadors site) became Hoyts Centre (holding Hoyts Cinemas 5 – 7): in 1997, the latter provided seating for 600, 400, and 400 patrons, but in April 1999 Hoyts Centre closed and the business was transferred to the Cinecentre (formerly Greater Union’s flagship).

Sources: Building permit, Battye 1459 (Folio 2)

Max D. Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, Sussex, 1986, pp.68-72, 77

Rodney I. Francis, ‘Thomas Melrose Coombe: a pioneer from vaudeville to talkies in Western Australia’, Kino, no.81, Spring 2002, pp.36-38

Vyonne Geneve, ´William Leighton, architect’, Kino, no.25, September 1988, pp.7-15

Jack Honnibal, ‘The MGM years at Perth’s Theatre Royal’, Kino, no.68, Winter 1999, pp.6-9; no.85, Spring 2003, p.43

Stage, Screen and Stars, West Australian, n.d. (1997?), p.12-4

Ross Thorne, Cinemas of Australia via USA, pp.74-76

Daily News, 28 September 1928; 23 July 1932; 20 March 1975; 24 August 1976; 13 December 1978

Everyone’s, 27 July 1927; 10 October 1928, p.22; 7 November 1928, pp.8-9; 14 November 1928, p.42; 21 November 1928, p.56; 29 January 1930, p.18

Film Weekly Directory, 1943 – 1971

Film Weekly, 18 January 1934, p.6, 4 July 1957, 2 December 1965, p.6

Kino, no.25, p.8, 14;

Post Office Directory, 1928 – 1949

The Showman, 15 February 1964, p.10

Sunday Independent 21 November 1976

West Australian, 1929 – 1997; 8 February 1972; 20 March 1975

Interviews (Ina Bertrand): Eric Nicholls (1985), Arthur Stiles (1985)

Interview (Ina Bertrand & Bill Turner): Jack Gynn (1981)

Interview (David Noakes): Keith Reddin (1978)

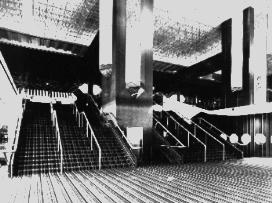

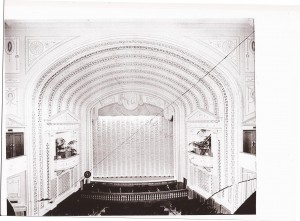

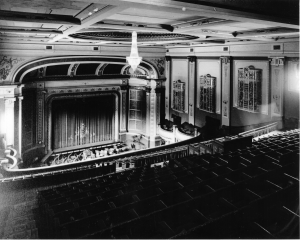

Photos: 2 architect’s designs, b&w, 1927, Everyone’s, 27 July 1927, p.84

interiors & exteriors, b&w, 1928, Everyone’s, 7 November 1928, pp.8-9; 14 November 1928, p.42; 21 November 1928, p.56; 20 February 1929, p.14 (stage show)

3 interiors (Ambassadors), b&w, 1929 (Battye 8292B/166-3 Series A; 4634P; 8292B 161-5)

2 exteriors (Ambassadors), b&w, 1932 (Battye 4587P, 4593P)

4 interiors, b&w, c.1970, Max D. Bell, Perth: a cinema history, pp.68-72

1 exterior (Wanamba Arcade), b&w, Sunday Independent, 21 November 1976

4 interiors (Hoyts Cinema 2), b&w, 1975, Daily News 20 March 1975

3 interiors (Ambassadors), b&w, 1963 (Ken Booth)

8 interiors, n.d, courtesy of Bill and Joan Gaynor

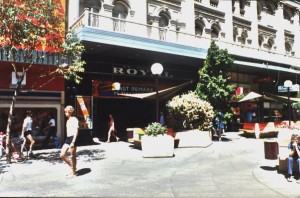

1 exterior (Hoyts Cinemas 2 & 3), colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

BEVANS AND GARDENS/ CRYSTAL AND GARDENS/ ALBION THEATRE AND GARDENS, 143-147 Wittenoom St, Perth (East)

This theatre and gardens, though located on the corner of Hill St on the outskirts of the City of Perth, was more like a suburban venue than a city one. It was built in 1935, and for several years (approx. 1945-1949), while it was conducted by N.J. (Noel) Bevan, it was known as Bevans Theatre and Gardens. There was provision for 500 patrons in the theatre and a further 500 in the gardens. In 1955, when it was taken over by Mrs S.Ray, it was renamed the Albion. When it closed in 1961, the building was converted for use by an automotive supplies company.

Sources: Max Bell, Perth – a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, Sussex, p.56

Film Weekly Directory, 1943/4 – 1960/61

Post Office Directory, 1935/6 – 1949

West Australian, 1937 – 1960

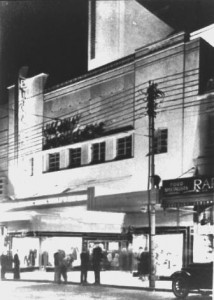

BRITANNIA/HOYTS CINEMA ONE, 676 Hay St, Perth

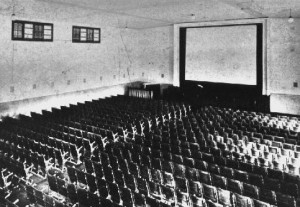

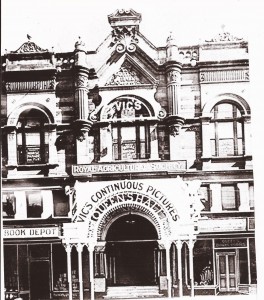

The third purpose-built hardtop cinema in Perth was the Britannia, which opened on 1 April 1915. It was built by a local businessman and managed by local showman Hamilton Brown in its formative years. Like the Pavilion, which initiated this policy, it was small, cheap and screened continuously from 11 a.m. till 11 p.m., and again like the Pavilion it occupied a shop-front and looked rather like the nickelodeons of earlier years in America:

The new premises are designed to form an up-to-date picture theatre. The length from the street front to the rear is 165 ft., with a breadth of 23ft. 6in. The hall is an exceedingly lofty one, provided with a large sliding roof and a maximum amount of fan and other ventilation, thus ensuring a low temperature even in close weather. Accommodation is provided in comfortable seats for 880 persons, of whom the dress circle will take about 260. An ornate vestibule is the external feature of the place, a door each side giving entrance to the stalls, and a double staircase leading to the dress circle and to the lounge and offices in front of the building. (West Australian, 2 April 1915)

The Britannia had a good reputation for quality programming. But with prices at 6d and 3d, it shared the Pavilion’s reputation for ´cheapness’, with the advantages and disadvantages which such a reputation brought with it. Nevertheless, it is not clear why the cinema closed on 18 May 1918, only three years after its optimistic opening. The premises were converted into shops.

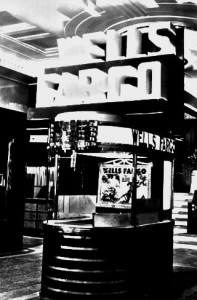

HOYTS CINEMA ONE

No films were shown on the site for five decades. Then in 1970 the ultra-modern City Arcade was built, incorporating among its shops and offices a cinema which was leased by Hoyts to become their Cinema One:

Hoyts’ new air-conditioned Cinema 1 atop City Arcade will be one of the most modern in Australia and will be in keeping with the colourful vitality of the arcade complex. Patrons will be able to buy their tickets either at the ticket office on the central arcade area on the Hay-St level or in the cinema foyer off the carpeted upper Hay-St level. The ticket box on the Hay-St level is a polygon shape…

The architects conceived the many-sided glass and laminated capsule, with its eye-catching reflecting surfaces, as a technological symbol. It harmonises with the nearby glass-sided lift and escalators that will take cinema patrons up to the next level to the foyer. In the foyer patrons will be greeted by usherettes wearing the theatre’s official colours – royal blue and lime green – and shown to their places inside the luxuriously finished 850-seat auditorium. Confronting them will be a 65ft. screen curved to a depth of 25 ft. It is designed for the screening technique called Cinerama, which Cinema 1 will be introducing to Perth. (Daily News, 11 November, 1970)

It opened on 23 February 1971. Cinema Two (and later Three, and, still later, Four) was built on the opposite side of the road, on the site of the former Ambassadors Theatre (and Theatre Royal). Cinema 1 was closed in 1990: the auditorium is still there, but the foyer and entrances were converted into shops in the arcade.

Sources: Max D. Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lews, Sussex, 1986, p.73, 77

Daily News, 11 November 1970

Film Weekly Directory, 1971

Kino, no.38, December 1991, p.27

David Coles, Letter to the editor, Kino 74, Summer 2000, p.5

Post Office Directory, 1916 – 1919

Sunday Times, 8 November 1970

West Australian, 2 April 1915, 1915 – 1991

Interview (Ina Bertrand): Arthur Stiles (1985)

Photos: 1 exterior (City Arcade), colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

CHINATOWN CINEMA, Piccadilly Square, Perth (East)

This cinema was opened in 1991, with 224 seats, and in 1992 was reported to be doing well, mainly with films imported from Hong Kong.

Sources: Jack Honnibal, ´The theatres of Perth 1939 – 1993′, Kino no.45, September 1993, p.28

Kino, no.34, December 1990, p.24; no.40, June 1992, p.26

CINECENTRE/CITY CINEMAS/CINECENTRE, 139 Murray St, Perth

After the success of the Town Cinema, Ace Theatres’ next city venture in collaboration with Greater Union was to purchase the old taxation building on the corner of Barrack and Murray Sts, and to build Perth’s first multi-cinema complex, the Cinecentre, at a cost of more than $2 million. As well as shops on the ground floor, and offices in the floors above, the building contained a coffee lounge and restaurant, and three cinemas, two with 500 seats and one with 300. These shared projection facilities, which could provide for 16, 35 and 70mm films. All three cinemas were entered through an imposing foyer in Murray St. The complex opened on 12 February 1974.

In the mid-nineties, seating was provided for 228 in Cinema 1, 500 in Cinema 2 and 507 in Cinema 3. In 1997 the complex was known as the Perth City Cinemas, but by 1999 it had reverted to the old name of Cinecentre.

Sources: Building permit, Battye 1459, Folio 2

Bob Parkinson, ´Field report’, Kino, no.41, September 1992, p.12

Jack Honnibal, ´The theatres of Perth 1939 – 1993′, Kino, no.45, September 1993, p.29

West Australian, 12 February 1974, 1974 – 2000

Interview (Ina Bertrand & Bill Turner): John Pye (1981)

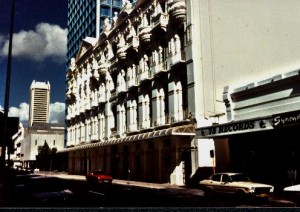

Photos: 1 exterior, b&w, n.d. (70s?) (Arthur Stiles)

1 exterior, colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

CINEMA CITY, 580 Hay St, Perth

In February 1978, TVW Enterprises Ltd completed purchase of the interests of City Theatres from the consortium which had bought the company in 1973. Soon after this, they announced plans to build a multi-million dollar shopping complex containing several new cinemas, on the old Haymarket site in Hay St, opposite the Town Hall.

At the time, this was the largest of the multi-cinema complexes, deisgned by architect Anthony Brand, and containing four new cinemas and provision for a fifth to be added in the future. Following tradition, a souvenir programme was issued for the opening, on Thursday 6 November 1980, providing the following description of the new building:

Cinema City was built at a time when almost every economic forecast said don’t. However, shrewd foresight and a bold decision by the TVW Board of Directors has seen Cinema City become a sensational new landmark of Perth…

Designed with extreme care, its reflective walls allow the old Town Hall to enjoy pride of place next to the new complex.

Rich multi-coloured carpets cover floor, steps, stairs and carry up for the full height of the inner walls.

The coffered ceiling increases the apparent height and suspended from it are fluorescent tubes sheathed in a glittering chromium plate…

Cinema City’s lobby opens into an enormous space over 14 metres (46 ft) high. The stunning effect of unlimited space is multiplied by each wall being sheathed by mirrors.

Chrome plated space frames adorned with lights, hang from the ceiling. The mirrors pick up the glitter and glamour of these features and reflect them on into what seems like eternity.

Another feature of the building was the shopping arcades, providing fashion shops, eating places, and services such as banks and hairdressers, with exits to Murray St and Barrack St as well as to Hay St. Dolby stereo sound systems were installed from the beginning. Also, as the souvenir programme describes:

For those unable to negotiate the stairs, a lift soars into the huge space, landing the elderly at foyer level and the incapacitated at a higher level gallery with wheelchair access to the backs of all cinemas.

This was one of the City Theatres properties taken over by Hoyts in 1988, and immediately put on the market (for leaseback). It was sold for a reputed $10 mill in 1994. The fifth cinema was never added, and in the mid-nineties, the four cinemas (still known as Cinema City, but now holding Hoyts Cinemas 1 – 4) held 494, 580, 394 and 790 seats. In 1999, Max Bell reported that: ‘The Cinema City shopping arcade and theatre complex has been sold to Perth investor Westpoint Corporation for approximately $13m. There are plans to develop the property for the third time.’ In 2002 it was reported that “a 20-storey hotel and residential complex” would be built above the cinemas, which would be retained.

Sources: Max D. Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, Sussex, 1986, p.78

Max D.Bell, ´Perth Cinema City’, Kino, no.33, September 1990, pp.16-17

Max D.Bell, ´Perth’s Cinema City’, Kino, no.78, Summer 2001, p.51

Jack Honnibal, ´The theatres of Perth 1939 – 1993′, Kino, no.45, September 1993, p.29

Australasian Cinema, 5 December 1980, pp.8-22

Kino, no.38, December 1991, p.27; no.49, September 1994, p.31; no. 67, Autumn 1999, p.31; no.80, Winter 2002, p.54

Sunday Times, 11 June 1978

West Australian, 7 November 1980; 1980 – 2000

Interview (Ina Bertrand & Bill Turner): Ray Cooper (1981)

Photos: interiors & exteriors, Australasian Cinema, 5 December 1980, pp.8-22

7 interiors, b&w, 1980 (Arthur Stiles)

1 exterior, b&w, 1980 (Arthur Stiles)

1 exterior, colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

1 exterior (side entrance from Barrack St), colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

1 exterior, b&w, 1980, Kino, no.33, p.17 (Max Bell)

CLUB ADULT CINEMA/CINE 1/SAVOY/CLUB X, 114 Barrack St, Perth

This was one of two cinemas run by Club Adult Cinemas, specialising in R-rated sex films, and offering live striptease three times a day. It opened in 1982, and was so successful that a second was later opened in Fremantle. These return to the small shopfront cinemas of the very early days, holding only 40-50 people. In 1991, when the Savoy cinema closed because of redevelopment of the Savoy Hotel site, the equipment of the Savoy was moved into these premises in the basement of the Club Emporium and screenings began again, though they were advertised only irregularly after that – as the Savoy in 1994-5 and as Club X in 1993 and 1996.

Sources: Kino, no.38, December 1991, p.26

Perth Telephone books, 1983-5

West Australian, 1982 – 1996

CREMORNE/BIJOU/ CREMORNE/PALACE/ CREMORNE, 111 Murray St, Perth

The complicated history of the name changes on this site is extremely difficult to disentangle. The first address for the Cremorne Theatre was ´off 31 Howick St’, at the time when Howick St was the name for Hay St, east of Barrack St. No.31 Howick St was the rear of 111 Murray St, and this was where the theatre entrance was situated till 1897, behind the Criterion Hotel. After that, entrance was from what later became Cremorne Arcade, running through from Hay St to Murray St.

Though it was called a ´theatre’, it was primarily an open air venue, of stalls and stages, in a garden setting similar to Ye Olde Englishe Fayre, at the other end of Hay St. There was an outdoor stage and a small indoor theatre, both used for musical and theatrical performances. The gardens adjoined the bungalow verandah of the saloon bar (of the Cremorne Hotel), and contained:

…palms, rockeries and a fountain, and the whole area was surrounded by a high wall painted with woodland scenery…

Spaced at intervals around the gardens were small roofed and latticed rustic kiosks, each lit up at night with coloured fairy lights, and each having a table and chairs inside for the convenience of private parties.

Over the front opening of each kiosk was painted the name of some well-known goldmining town such as Coolgardie, Boulder, Kanowna, Kookynie and many others.

Two German waiters in evening dress hurried to and fro with their trays of drinks, clinking glasses which always rattled with the broken ice blocks inserted before the drinks were served. (West Australian 3 January 1953, p.12)

In late 1896, the theatre was owned by Mrs Annie Oliver, and leased to King Hedley, who offered traditional vaudeville programmes. It was the second venue in Perth to present films, three weeks after Ye Olde Englishe Fayre. ´THE GENUINE CINEMATOGRAPHE and COMBINATION PICTURES’ ran for a season of five weeks from 12 December 1896 to 18 January 1897. The programme was presented twice each evening, starting at 8.30 and again at 9.30 p.m., and there was a matinee on Saturdays at 3 p.m. The machine was probably a Lumiere, as the films listed in the programme were from among those distributed by the Lumiere Company: Soudanese Diving, Grand Steeplechase, Buckjumping horse, Arrival of a train at a station, A Game of Cards, Paris Street Scene. Entrance to the films could be obtained either directly through the main theatre entrance or through the gardens attached to the theatre, where the usual vaudeville performance was continuing. The season was successful, but, like the Fayre grounds, the Cremorne Gardens closed during the off-season, and the theatre returned to traditional vaudeville shows.

The following summer, both Carl Hertz and Charles Harper successfully presented their films at the Cremorne before going on to Fremantle, Hertz from 16 to 28 August 1897, and Harper from 1 to 6 November 1897. After the hiatus of 1898-9, film programmes in summer seasons resumed, with Clarke’s Royal Biograph in August 1899, followed by other presentations over the next three summers. These included, among others, the Royal Biograph from 19 to 28 August 1899, and again 17 March to 2 April 1900, Heller’s Mahatma Co 13 to 19 October 1900, American Biograph 28 to 31 October 1901, and coronation pictures by Optigraph 18 October to 15 November 1902. For a few months in the summer of 1902-3, the theatre was advertised as the ‘Bijou’, but the Cremorne Gardens opened on Boxing Night 1902 as usual. Jones and Lawrence were associated with the venue from early 1900 till 1903. It appears to have been unoccupied for some time, and to have re-opened late in 1904:

Under the title of ´The Palace Gardens’ what was once the most popular place of outdoor entertainment in Perth, viz. Cremorne Gardens will be thrown open to the public next Saturday evening when the first of a series of entertainments will be presented.

The ´Palace Gardens’ will be under the direction of Mr Leonard Davis…An attractive item will be the pictures projected by Edison’s latest invention for producing moving pictures and known as the Chronojector. (West Australian, 29 October 1904)

Davis presented films as part of the vaudeville offering of the gardens, with weekly changes of programme, till 3 February 1905. Before the end of the season, Daudet’s Parisien Living Pictures presented a short season, then the gardens closed again till the following summer. Before the next season a major refurbishing took place:

On Thursday next the Palace Gardens and Theatre will be re-opened for the summer season by Mr Leonard Davis. For some time past a large staff has been engaged in beautifying the gardens, and at the present time there are ample evidences of the work bestowed upon them. The lawns are beautifully green, the small garden plots are gay with flowers and shrubs, and the interior of the teahouses presents an attractive appearance. For the occupation of patrons who purchase 3s and 2s tickets, the whole of the lawn space will be available, while the gallery and promenade will be reserved for purchasers of 1s tickets. Venetian deck chairs, with canvas backs, specially designed for ease and comfort, and painted white, are being manufactured, the dais for the orchestra is enclosed with handsome red curtains, hung on nickel railings, and the members of the orchestra, and the attendants, will be attired in white uniforms. The theatre will also be opened on Thursday next, and will be conducted on similar lines to those which obtain in the American music halls. A large number of novelties, including a waxworks exhibition of 50 figures, penny-in-the-slot machines of all descriptions, stereophones, picturegraphs, and two boxes of radium have been imported and will be on view in the theatre.. (West Australian, 11 November 1905)

The stereophone provided a short film of a singer performing, synchronised with a gramophone reproduction of the singer’s voice, and in a later advertisement it was made quite clear that among the moving novelties available in the theatre (called the ´Palace of Amusements’) was also a traditional cinematograph (West Australian, 11 December 1905).

The summer seasons of 1905-6, 1906-7, 1908-9 all appeared to be very successful, and all employed a cinematograph as a part of the varied offering for some or all of the time. In December 1906 Harry Rickards had taken over the lease, but Leonard Davis remained as sub-lessee and the policy of the management did not appear to change. A correspondent in the West Australian praised Rickards for withstanding the temptation to open on Sunday, a practice which was considered by the writer to undermine the conditions of the working man (West Australian, 1 January 1909).

From 1910 onwards, films seemed to fade out of the theatre’s programmes, appearing less and less often among the vaudeville offerings.

In July 1910, the Cremorne Theatre suddenly re-appeared in advertisements, apparently concurrently with the Palace Gardens. This confusion of names cannot be sorted out from extant references, but it seems likely that in the earlier years the venue had depended mainly on the summer season in the gardens, and that the indoor theatre had existed just as an adjunct to the gardens, open for special seasons during the winter months, but apparently not consistently. During this period, the gardens gave its name to the theatre, even though the original ´Cremorne’ was named after the adjacent hotel, which continued to operate under the same name throughout the period. Round 1910 it appears that the theatre began to have an independent life, perhaps under the expert guidance of Harry Rickards. So it took its own name again as the Cremorne, and then the whole venue returned to the original name.

Leonard Davis had had a long association with film as a part of vaudeville offerings, and in December 1911 had announced his intention to ´merge the entertainment into one of vaudeville and biograph variety’ (West Australian, 23 December 1911). However, when he opened the Palace Gardens for the summer season on Christmas night 1912, he had changed his mind, and announced that he would now programme only vaudeville, without films. It is possible that as, by this time, films had purpose-built cinemas for their presentation, he felt that audiences expected a full programme of one or the other. In any case, from that time films no longer appeared at the Cremorne Theatre or the Palace Gardens, though the venue continued till the summer season 1917-18.

Sources: Stage, Screen and Stars, West Australian, n.d. (1997?), p.20

Post Office Directory, 1897 – 1928

West Australian, 11 November 1905, 3 January 1953 p.12, 17 January 1953 p.15, 14 January 1956 p.23, 1896 – 1920

Photos: 1 exterior (Cremorne gardens), b&w, 1896, West Australian no.4224 (17 January 1953, p.15)

1 exterior (Cremorne gardens) b&w, 1866? Alexandra Hasluck & Mollie Lukis, Victorian and Edwardian Perth from Old Photographs John Ferguson Pty Ltd, St Ives, 1977, plate 57

EMPIRE PICTURE PALACE/KING´S PICTURE PALACE/MELBA PICTURE HALL, 227 Murray St, Perth

Empire Pictures, directed by F. C. Clarke-Cottrell, had been screening very successfully in the Perth Town Hall from May 1910. They announced, towards the end of 1911, that they intended to build a new picture palace in the city, and ran a competition for a name for the new building: the suggestion that they had made their name with ´Empire’ and that they could do no better than stick with this, was accepted. During 1911, Shierlaw and White constructed the building, valued at £2,625, for owner H.Cochrane, and on 16 December 1911 this first purpose-built hardtop cinema in Western Australia was opened:

The Empire Pictures management gave the first entertainment in their new premises – the Empire Picture Palace, central Murray St – on Saturday evening. The new theatre is built of brick, and can comfortably accommodate 1,500 people. The walls are finished with white plaster, and the ceiling is of stamped metal. Apart from a host of other good points, the premises are fitted with a sliding roof, a lounge, ladies’ retiring rooms, and a refreshment hall. Provision, too, has been made in case of fire for the rapid exit of patrons, by a number of side escape doors, which lead into a commodious right-of-way and thence into the street. The attendance on Saturday night was a highly-gratifying one, a circumstance which the programme well justified. …Features of the initial performance were the musical numbers given by the Empire Orchestra of ten players under the baton of Conductor T.G.Williams. During the evening, too, Miss Pearse gave one of her popular songs. (West Australian, 18 December 1911)

Despite this glowing review, which concluded with a promise that performances would continue nightly, no further advertisements for the Empire Picture Palace can be found. Instead, by April 1912 it appears that the theatre has been taken over by another company and renamed.

King’s Picture Gardens, which opened in December 1908 at the foot of William St, was conducted by the King’s Picture Co Ltd, originally under the direction of Charles Sudholz, then, from late 1910 by Brown and Dease, and from December 1910 by Dennis Dease alone. King’s Pictures also screened every Monday from 13 February 1909 at Midland Junction, and then extended their provincial exhibition to weekly screenings at Fremantle on Saturdays, York on Tuesdays, Northam on Wednesdays, Bunbury on Thursdays and Collie on Fridays. By the end of the year this provincial circuit, though still known as King’s Pictures, seems to have been conducted independently of the Perth operation.

All of these were highly successful, despite the changes in management – sufficiently successful for Dease to decide to venture into permanent exhibition in the city, rather than be satisfied with the summer seasons available through the gardens. The last performance by the company at the King’s Picture Gardens was in April 1911, and the gardens did not re-open till January 1912, now under the direction of Cozens Spencer, and with a new name – the Esplanade Picture Gardens. Meanwhile, Dease had acquired the lease of what had been the Empire Picture Palace in Murray St, and he opened here in April 1912, advertising variously as King’s Picture Palace or King’s Theatre. He obtained his product through J.D.Williams, and presented the output of the Melbourne-based Lincoln-Cass Company very successfully during 1912. The sliding roof of the hall was a selling point during the hot summer, but early in 1913 presentations again ceased.

The hall was re-opened, ´under entirely new management and redecorated throughout’ (West Australian, 7 June 1913), in early June, under the direction of H.H.Cockram, and now known as the Melba Picture Hall. The new management continued to feature Australian productions, including a West Australian film of the Kalgoorlie Cup Meeting in September 1913, and Life of a Jackeroo in January 1914. However, there is no record of how successful the enterprise was, nor of why it closed permanently on 2 August 1914.

Sources: Perth City Council records, PTL F14, 1911

Post Office Directory, 1912 – 1914

West Australian, 18 December 1911, 1911 – 1914

FLIGHT DECK, 154 James St, Perth

This adult cinema advertised for a short time in 1984 only

Sources: West Australian 1984

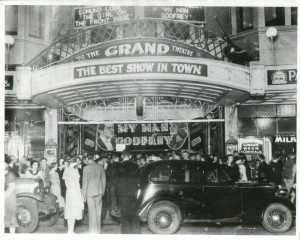

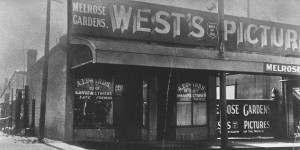

GRAND, 164-168 Murray St, Perth

This theatre was built by entrepreneur Thomas Coombe and purchased from him by his sons Thomas Melrose (later Sir Thomas) Coombe and James

Lean Coombe. It opened with a charity gala performance in aid of Wounded Soldiers, and with a ´Soldiers Orchestra’, on 20 September 1916. The manager was Thomas Coombe (jnr), a lawyer, who had entered the film business in Perth as a partner in the local firm of Empire Pictures with F. C. Clarke-Cottrell and Thomas Shafto. The company had screened in the Perth Town Hall in 1910, and at Subiaco (in the King’s Hall and on the oval) during 1910 and 1911. The partners had then gone their own ways, each into a career in the film industry, Thomas Coombe beginning as attorney for West’s, managing the Melrose Gardens and later the Melrose Theatre. The Grand was his first independent venture, and he quickly made a success of it.

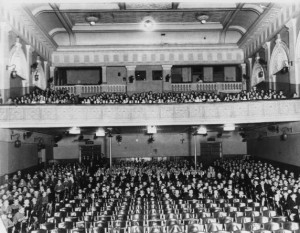

In comparison with the live theatres of the time it was small – 1100 seats, about the same size as its competitors, the Pavilion, the Palladium, the Britannia and the Majestic. All five opened during World War One, and followed similar policies of continuous screenings and cheaper admission than the live shows. The Grand, however, from the beginning aspired to a rather more lofty image than the others. It had a windlass-operated sliding roof, like the more prestigious live theatres, and also shutters on the side walls which could be removed for ventilation like the semi-open-air theatres.

When Coombe went into partnership with Union Theatres’ West Australian branch, the Grand became an important part of the Union Theatres chain.

Around 1920 Coombe had employed a young man named Hamilton Brown to manage the Princess (Fremantle) for him. Brown did so well in this position that as Coombe involved himself less and less in the daily affairs of the theatres he passed over more and more to the younger man, finally making him manager of all Coombe’s various theatrical concerns. When Coombe retired, Brown was appointed manager for all Union Theatres’ interests in the state. It was under his management that the Grand was wired for sound in 1929 (and abandoned its orchestra), and in April-May 1932 became an all-British house, a showcase for the most prestigious of the British films.

However, in 1929 at the height of the depression, the theatre had been sold for £82,000 as a speculation to Town and Suburban Properties Ltd, and leased back to continue to run as a Union Theatre. By the beginning of 1932, the financial crisis which was to force Hoyts and Union Theatres into an amalgamation as General Theatres, was being felt in Western Australia also. Union Theatres fell behind with the rent for the Grand, the bailiffs were called in and their tenancy was abruptly halted. This was a decision of James Stiles, on behalf of the owners of the property, of which he was a partner.

Town and Suburban Properties Ltd was a company owned by four families – the Stiles, Taylor, Davenport and Vivian families. Stiles, who had an interest in suburban theatres in South Perth, was the only one with any experience in film exhibition, but he was noted also for his resourcefulness and energy, and when he urged the company to take the risk, in the belief that he could sustain the theatre during the hard times ahead better than any tenant could, they agreed. On 25 August 1932 a new company, formed substantially of the same shareholders as Town and Suburban Properties, was formed – the Grand Theatre Co – specifically to manage the Grand Theatre as a functioning cinema. And, instead of appointing a manager, Stiles took on the task himself. He was so successful that the company went on to lease and build other theatres, eventually becoming for a time the largest local chain, and even larger in the state than the eastern-based national chains of Hoyts and Union Theatres.

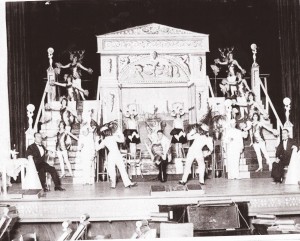

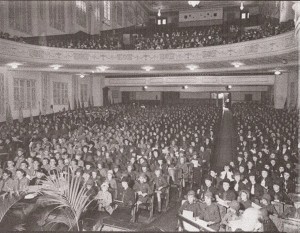

As promotion for the film Little Orphan Annie, the Grand Theatre Company held an ´orphans picnic’: they invited the residents in all the orphanages in Perth to a day out, including a film screening at the Theatre Royal. This was such a success that it continued annually for many years, with the film presentation usually at the Grand.

Over the years, very little change was made in the façade of the Grand: brickwork was painted over, a neon sign added in the manner traditional to cinemas (down the length of the façade), and the ornate metal verandah replaced with one of cleaner, more modern lines.

Inside there was more change. The first major reconstruction took place in 1938:

The supporting pillars in the stalls have been taken away, and throughout the theatre provision has been made for the comfort of patrons by considerably widening the space between the rows of seats. What were previously two small landings upstairs have been joined together and enlarged to make an attractive smoking lounge. Extensive alterations have been made to the walls which have been repainted in pastel shades predominantly green. A feature of the new theatre is the lighting system, which is done with neon lights. The Grand is the first theatre in Australia entirely illuminated by neon lights, and the effect is most pleasing. (West Australian, 17 December 1938)

When it was re-opened on 16 December 1938, after only four weeks’ work had completely transformed the interior, stress was placed on its reputation as a ´family theatre’ and the ´homely’ design and comfort it offered. There was considerable pride expressed in the fact that the renovations had been done using as far as possible West Australian labour and materials. By now, however, it had to compete against the picture palaces of the thirties, and its reputation had sunk to that of a ´churn house’ – one of the continuous theatres that ´churn’ out sessions.

By the time of the second major renovation in 1959, the Grand Theatre Company had been transformed into City Theatres Pty Ltd, in recognition of the wider activities of the company, though the management, in personnel and policy, had not substantially changed. This renovation was extensive:

The Grand Theatre, home of British pictures in Western Australia, has been modernised and refurbished at a cost of £15,000 to make it one of the attractive showcases of the West Australian capital. In the modernisation scheme planned by architects Hobbs, Winning and Leighton a new lounge foyer has been created.

Lounge foyer is attractively carpeted and painted, with decor set off by the wood panelling of the walls.

Seating has been provided and there is also a modern and well-stocked candy and soft drink bar.

A cooling system operating on an air filter system has also been installed, while a new suspended ceiling in the theatre lends a modern touch to the building and has improved sound throughout the theatre.

Similar style ceiling has been fitted in the lounge foyer and in the theatre’s entrance lobby. (Film Weekly, 15 January 1959)

It was not fully air-conditioned till 1961.

In 1973 City Theatres was taken over by a consortium consisting of local television company TVW Ltd, Swan Television and Michael Edgley International Ltd. In August 1978 TVW Ltd bought out the other partners, though again there was little change in management, as Arthur Stiles, nephew of James Stiles, remained as Managing Director under the consortium and as Manager under TVW.

By now, the theatre which had changed hands for £80,000 in 1928 was worth £900,000, not so much for the building, which had long since become outmoded, as for the prime position in the central city. Each modernisation, providing more spacious accommodation for patrons, had also reduced the number of seats available, till by the end it could only accommodate 721. Fortunately, the trend in cinema building in the seventies was towards smaller, more intimate theatres anyway, which was probably all that kept the Grand going in its later years. It closed on 6 November 1980, the day that the company opened Cinema City. City Theatres retained their offices in the front of the building upstairs, while the foyer and auditorium was used for a complex of restaurants and fast food outlets. The building was demolished in March 1990.

Sources: Building permits, Battye 1459, Folio 2

Max D. Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lews, Sussex, 1986, pp.78-79

Rodney I. Francis, ´The Coombe family of Perth’, Kino no.34, December 1990, pp.12-17; ‘Thomas Melrose Coombe: a pioneer from vaudeville to talkies in Western Ausrtalia’, Part 2, Kino no.80, pp.46-48.

Jack Honnibal, ‘Perth’s Grand Theatre in its heyday’, Kino, no.64, Winter 1998, pp.26-29

Stage, Screen and Stars, West Australian, n.d. (1997?), p.20-21

Ross Thorne, Cinemas of Australia via USA p.163

Australasian Exhibitor, 15 July 1954, 5 December 1980

Everyone’s, 23 January 1929, p.24; 20 February 1929, p.6,14; 4 September 1929, p.32

Film Weekly, 15 January 1959, p.1

Film Weekly Directory, 1943/4 – 1971

Kino, no.32, June 1990, p.23

Post Office Directory, 1917 – 1921, 1929 – 1949

Sunday Times, 17 April 1932, 24 April 1932, 11 January 1959

West Australian, 20 September 1916, 24 May 1932, 15 December 1938, 17 December 1938, 1916 – 1980

Interview (Ina Bertrand): Arthur Stiles (1985)

Interviews (Ina Bertrand & Bill Turner): Ray Cooper (1981), John Pye (1981)

Arthur Stiles scrapbook

Hamilton Brown scrapbook

Photos: 1 exterior, b&w, 20s, West Australian no.3394

1 exterior, b&w, c.1921/2, Battye 3183 11811P

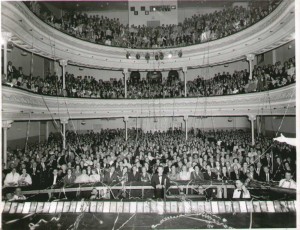

1 interior (auditorium – orphans picnic audience), b&w, 1930s (Arthur Stiles)

2 exteriors (orphans picnic audience), b&w, 1930s (Arthur Stiles)

2 interiors, 2 exteriors, b&w, 1930s, Jack Honnibal, ‘Perth’s Grand Theatre in its heyday’, Kino, no.64, Winter 1998, pp.26-29

3 interiors (foyers), b&w, 1960s (Arthur Stiles)

33 exteriors & interiors, colour, 1980 (Roy Mudge)

1 exterior, b&w, n.d., Australasian Cinema, 5 December 1980, p.8

1 exterior, colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

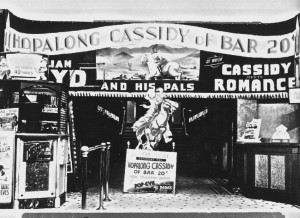

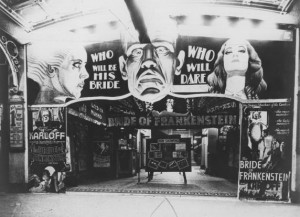

exploitation campaigns, b&w, various dates, Arthur Stiles

GREEN LAWN PICTURE GARDENS, 489 Hay St, Perth

This must have been the shortest-lived of all the picture businesses in the state. It opened on Saturday 21 October 1916, conducted by J. F. Mulqueen, with accommodation for 2000, and screening Clement Mason Super Features. The orchestra of six professional musicians was under the direction of the “Musical Gardiners”, and prices were the standard rates for picture gardens of 6d and 1/- for adults, children 3d. Veteran showman Norman Cunningham remembers it as being on the south side of Hay St, near Irwin St (West Australian, 4 September 1980), which possibly means that it occupied the site used in the summers of 1897-8 and 1898-9 by the Olde Englishe Market Place and Fayre in aid of the Children’s Hospital (not to be confused with ´Ye Olde Englishe Fayre’ at the corner of Hay and King Streets – or that at 66 South Terrace, Fremantle).

On 4 November 1916, prices were reduced to 3d for adults to all parts, and 2d for children, and on Wednesday 8 November the advertisements claimed that the venue was winning patrons with excellent programmes and prices “the lowest in the city.” This may, however, have been a desperate bid to boost a flagging enterprise – it was not again advertised in the city papers, and apparently faded away not long afterwards.

Sources: Post Office Directory, 1917

West Australian, September – November 1916, 4 September 1980

Interview (Ina Bertrand & Bill Turner): Norman Cunningham (1981)

KING´S PICTURE GARDENS/ ESPLANADE PICTURE GARDENS/CAPITOL, 2-10 William St, Perth

On 26 December 1908, the first premises in Perth designed and built exclusively for the presentation of moving pictures were opened – King’s Picture Gardens, on the Esplanade, at the foot of William St:

The seating capacity is 2,000 and it is stated that every effort has been made to secure the comfort of intending patrons, in the way of refreshment kiosks, retiring rooms, etc… The grounds have been tastefully laid out and are surrounded by tinted walls surmounted by artistic trellis work. The auditorium has a well-graduated slope towards the south end, thus ensuring a good view of the large enamelled screen from all parts. (West Australian, 19 December 1908)

…the walls are kalsomined in a delicate shade of salmon pink, topped by artistic trellis work treated in a sky blue medium… the refreshment rooms have been designed in the manner of Swiss Chalet architecture and the tout ensemble may be regarded as highly artistic. (West Australian, 22 December 1908)

Despite the appreciation shown by patrons of the delightfully cool open-air environment in another hot Perth summer, and of the right to smoke their pipes during a performance, the first screening still left something to be desired:

An appreciable improvement might be made by altering the screen, which is of tin, white painted. The shine of the paint created unnatural and undesirable effects in many of the pictures. It may be added that the noise effects produced behind the screen to give realism were an unnatural exaggeration and an aggravation to the audience. (West Australian, 28 December 1908)

These problems, however, were soon overcome, and the premises were open for three summer seasons, with increasing success. For the third season, a gallery was added, increasing the capacity of the gardens to 2,900. But still the papers reported capacity houses: ´…seating capacity taxed to the utmost.’ (West Australian, 21 November 1910)

Charles Sudholz had been the first managing director of the King’s Picture Company which had built the gardens, but by the next summer he had been replaced by Brown and Dease, and from 19 December 1910 by Dennis B.Dease alone. Despite (or perhaps because of) this success, Dease moved on, and opened at the King’s Picture Palace (formerly Empire Picture Palace) in January 1912.

By then, Cozens Spencer had bought the gardens at the foot of William St. These were dark for the start of the 1911-12 summer season, but re-opened in late December, 1911, as the Esplanade Picture Gardens:

The management of the Esplanade Picture Gardens (recently acquired by Spencer’s Pictures, Ltd) announces that it is their intention of opening this popular open air place of entertainment at the beginning of next week if not sooner.

The premises have been entirely rebuilt, and the whole arrangement altered in such a way that every person seated will have a clear and uninterrupted view of the screen. For the most part leather cushions will be provided, and the accommodation as a whole will, it is stated, be infinitely superior to anything of the kind yet provided for out of door entertainments. (West Australian, 18 December 1911)

After four visits to the state, Cozens Spencer had leased the Theatre Royal in 1911 for a permanent exhibition venue, and he used the Esplanade Gardens for a short season each summer to take advantage of the warm weather. During the Gardens season, patrons could see the same programme either there or at the Theatre Royal, as they preferred.

The Gardens continued to advertise as Spencer’s Esplanade Gardens until early 1920, long after Spencer himself had left the state. By then, it was the last open-air venue left in the city area, though others opened later, including the Rialto Cinema Gardens, and the Olympia Gardens in Hay St.

In 1912 Spencer’s Pictures had become a part of the Union Theatres group, and in 1920 this group had announced its intention of building showcase cinemas in Melbourne and Sydney first, then Brisbane and Adelaide. In May, Stuart Doyle, managing director of the company, visited Perth to announce plans for a similar building in the West Australian capital. The Prince of Wales was not completed till 1923, but meanwhile the Esplanade Gardens was not re-opened, and the site remained vacant for several years.

CAPITOL

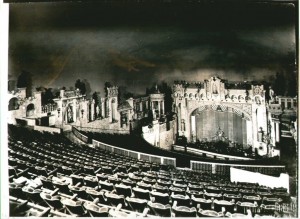

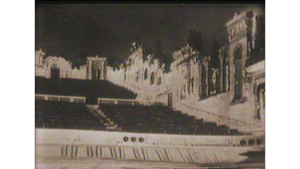

In 1926, plans were lodged with the West Australian Board of Health for a complex on the site, designed by architects Poole and Mouritzen. In addition to a theatre, the four-storey building was to house two garages, shops and offices, as well as a cabaret and a winter gardens (Everyone’s, 15 May 1929, p.26): the theatre was located on the northern side of the site, facing William St, while Temple Court buildings occupied the southern section, curving around into the Esplanade.

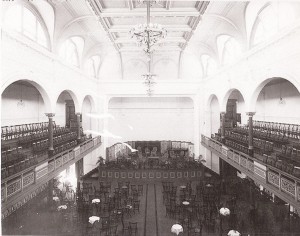

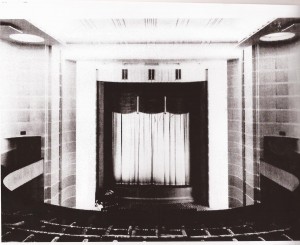

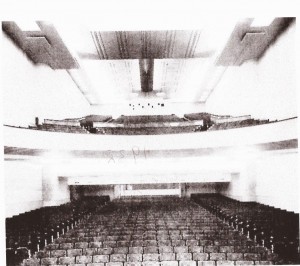

Total cost was over £100,000, and the building was not completed till 1929. The whole scheme was the brainchild of entrepreneur Dr A. J. Wright, who formed Temple Court Buildings Ltd expressly for the purpose. Stanley L. Wright then leased the theatre from the company, and appointed Jack Coulter as manager, Harry Cross as Director of Music, J.J.Collins as presentation manager (in charge of the live presentations) and Miss Leah Miller ballet mistress. The Capitol opened 4 May 1929, to enthusiastic reviews:

An impression of chaste solidity is conveyed to the observer from outside, and the interior’s grand splendour confirms it. Space is abundant. The mezzanine becomes not a passageway, but a roomy ante-chamber, the lounge is a luxurious drawing-room apart, and in the auditorium the seating accommodation has suffered by an attempt to give adequate room for all. Acoustics, ventilation and conveniences – are all well-nigh perfect, and a close examination of the interior reveals master craftsmanship worked out to the merest detail of decoration. (West Australian, 1 May 1929)

Built on solid, massive lines, with lofty roof-top supporting a marvellous chandelier, the decorative embellishments are on refined lines. Blue and gold, mostly gold, furnish the colour scheme. The ventilation is controlled by massive shutters on each side of the auditorium, covered by beautiful ornaments which house many lighting effects. It is from these side panels, standing out from the walls, that come the spotlights which give the light-painting effect to the chandelier, which is capable of illuminating the whole auditorium without aid from side or other lighting.

Lounge and mezzanine floors vie one with the other. On the passage ways to the lounge brilliant colours are illuminated by hidden lighting, and the transformation to a delightful drawing room is remarkable. Comfort is everywhere. There are corners where the light is a bit dim, cozy corners with soft rounded seats, coloured windows above the head.

The boudoir, the cloakrooms, all the appointments of the upper portion of the theatre, invite comfort. (Everyone’s, 15 May 1929, p.26)

However, eighteen months later Wright was forced to admit failure. Despite claims in early publicity that he had secured contracts with RKO for a supply of films for the theatre, he was never able to obtain sufficient first-class product to keep a cinema of over 2,000 seats viable in the city centre, even though he continued to advertise as ´Westralia’s premier extended season talking picture theatre’ (West Australian, 2 January 1930).

In addition, the Photophone sound system was the only one of its kind in Western Australia, causing problems of servicing and increasing expense. This had eventually to be replaced with a standard Western Electric system for the sake of economy. By then, however, the lease had been taken over by Hoyts.

For the next few years, the theatre shared the mixed fortunes of that company, becoming one of the General Theatres chain in 1934, and of Westralian Cinemas in 1936. In the forties the lease was taken over by Fullers, and then by General Amusements Pty Ltd, Garnett Carroll’s firm, and so it ceased to be programmed exclusively as a cinema. Its design, fully described by Ross Thorne, included a stage, and so it was used for concerts and theatrical performances:

…from Laurence Olivier to Jazz Jamborees, from the Chinese Classical Theatre to the Harlem Blackbirds, from Ice Capades to Ralph Richardson. The theatre has housed dancing school concerts, religious meetings, magicians, hypnotists and a variety of one-man shows. (Film Weekly, 19 November 1959, p.9)

The auditorium was ornate and lavish, aiming at the ultimate in comfort, even luxury. But the stage provision was not adequate for the larger companies and presentations, so in 1961 Edgleys, who by now had taken over the lease, decided to improve this aspect of the theatre. A fire in 1962, which destroyed stage and fittings, ended this plan, and in 1966 the premises were bought by the then Lord Mayor of Perth, T. E. Wardle. He announced plans to re-open the theatre, but accepted a further offer within months of purchase, and the theatre was demolished in 1967, to make way for a multi-storey office block.

From the very beginning, this site seemed dogged with misfortune, and not able to realise its potential. There were many sorry to see the magnificent building torn down, but few of those who had been actively involved in its history had found the experience really satisfying.

Sources: Tom Austen, The streets of old Perth, St George Books, Perth 1989, pp.104-5

Max D. Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, Sussex, 1986, pp.74-77

Stage, Screen and Stars, West Australian, n.d. (1997?), pp.15-17,38

Ross Thorne, Cinemas of Australia via USA, pp.102 – 109

Daily News, 12 September 1966

Everyone’s, 11 July 1928, p.20; 18 July 1928, pp.15,21; 15 May 1929, p.26; 27 August 1930, p.7; 27 March 1929, p.18; 8 May 1929, p.20; 15 May 1929, p.26

Film Weekly, 19 November 1959, p.9

Film Weekly Directory, 1943/4 – 1964/5

Post Office Directory, 1911 – 1949

West Australian, 22 October 1962, 1908 – 1958

Interviews (Ina Bertrand): Ken Booth (1978), Chris Spivey (1978)

Photos: 2 exteriors, b&w, 1906/191?, George Seddon & David Ravine, A city and its setting: images of Perth, Western Australia, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 1986, pp.182-193

1 exterior (Esplanade gardens), b&w, c.1912, West Australian no.5956

1 exterior (Esplanade gardens), b&w, c.1912, Alexandra Hasluck & Mollie Lukis, Victorian and Edwardian Perth from Old Photographs John Ferguson Pty Ltd, St Ives, 1977, plate 61

1 exterior (Esplanade Gardens), b&w, n.d. (Ross Thorne)

1 interior (Capitol during construction), b&w, 1928, Everyone’s, 18 July 1928 p.15

8 interiors (Capitol), b&w, n.d., Ross Thorne, Cinemas of Australia via USA, pp.102 – 109

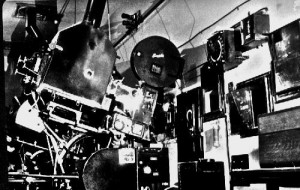

1 interior (Capitol biobox), b&w, 1935 (Ken Booth)

1 exterior (Capitol), b&w, 1930s, Tom Austen, The streets of old Perth, St George Books, Perth 1989, p. .105

2 exteriors (site of Capitol), b&w, 1981 (Bill Turner)

2 photos of shows, n.d. donated to AMMPT

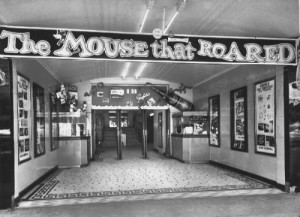

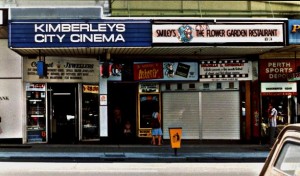

LIBERTY/CITY CINEMA/KIMBERLEYS CITY CINEMA/KIMBERLEY/LIBERTY, 81 Barrack St, Perth

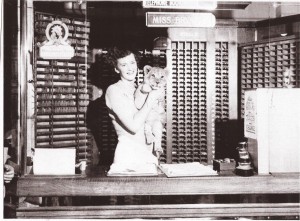

Lionel Hart first visited Western Australia in his capacity as salesman for Universal Pictures. He later, however, accepted the position of director of the orchestra at the Prince of Wales. In the fifties he attempted to distribute ´continental’ films in Western Australia. At that time, cinemas such as the Sydney and Melbourne Savoys were sustained by the huge post-war influx of European migrants and by the growth of the film society movement which created an audience for what the trade called ´art’ films. Neither of these audiences was as strong in Perth as in the east. But Hart saw a potential market, and decided that, rather than try to break into the established circuits with such films, he would open a specialist cinema comparable to those in the east.

He converted the first floor of an office building into a small theatre, seating 450 patrons, and the Liberty opened 4 March 1954, with a charity premiere of Rigoletto, followed in later weeks by mainly Italian and French films. The premises were also used by the Perth Film Society for Sunday night screenings. In 1955 there were three screenings a day, and by 1958 this had grown to four, with more varied programming in the later years.

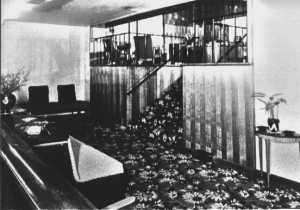

The cinema survived the arrival of television in Perth in 1959, then on 1 February 1961 the building was completely gutted by fire. It was rebuilt and re-opened in June that year, continuing with the same policy. A distinctive feature of the new building was the ´garden lounge’:

Situated at the rear of the 450-capacity theatre, the lounge will give patrons inside the impression of being seated in a garden.

They will be able to smoke and watch the film through a special glass partition window. (Sunday Times, 28 May 1961)

This did not, however, protect the theatre from fire, which again struck in 1971, requiring less extensive restoration, but still closing the premises for several months.

By now, the company that Hart had established, Independent Film Distributors (W.A.), was running the Savoy and the Windsor (Nedlands) as well as the Liberty, and was importing films for these theatres and distributing them in the rest of the state as well. This company was taken over in the late seventies by Frank Lloyd, whose background in the Savoy cinemas in Melbourne and Sydney ensured that the policy of continental programming would continue. However, the cinema industry depression finally made its presence felt, and even the fortunes of the specialist cinemas fluctuated till on 9 February 1978 the Liberty closed. Of Frank Lloyd’s chain, the Windsor survived as a prestige suburban cinema showing mainly ‘art’ films, and the Savoy became an R-movie house.

On 7 July 1978 the City Cinema opened on the Liberty/Kimberley site with a return season of A Star is Born, and from the end of July the theatre was known as Kimberleys City Cinema. It became first another R-movie house, then a repertory cinema for the Valhalla company, which was doing well in the east with classical revivals and specialist first runs.

By 1985, it was being run by a partnership of Bob Yelland, John Marsden and John Parker. It was still slightly seedy, known simply as the Kimberley, and presenting second runs of recent and popular films, and seasons of children’s films in the school holidays. In 1986 a freshening up of the venue included recarpeting and repainting the entrance, hanging a new sign outside, and re-siting the ticket box. However, patronage continued to decline, and in January 1987 a consortium took it over, to screen first-run Asian (Chinese-language) films. Then it closed for renovations.

In December 1992, the renovated cinema was re-opened, with 390 seats and reverting to the old name of Liberty. For a while, Malcolm Leech (who was running similar screenings at the Piccadilly) was screening Hong Kong movies there, on week-nights and at weekends from about 2 p.m. till 1.30 a.m. The candy bar was completely rebuilt in the small foyer. The first years were successful, but Chris Simmonds attributes the decline to ‘the black market in Asian Moveis and the Asian love of Western Movies’. A short-lived excursion into live theatre did not rescue the venture, which reverted to screening Chinese-language films in early 1997, but by October this closed and the cinema was again available for lease.

Sources: Building permits, Battye 1459 (Fol.2)

Max D. Bell, ´Liberty/Kimberley’, Kino, no.20, June 1987, p.4; ´Perth Liberty’, Kino, no.60, June 1997, p.11.

Max D. Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, Sussex, 1986, pp.82-83

Jack Honnibal, ´The theatres of Perth 1939 – 1993′, Kino, no.45, September 1993, p.29

Australasian Exhibitor, 1960 – 1968

Film Weekly 1957 – 1961; 9 February 1961, p.1 (photo of Lionel Hart)

Film Weekly Directory, 1953/4 – 1971

Kino, no.15, March 1986, p.22; no.19, March 1987, p.23; no.40, June 1992, p.26; no.43, March 1993, p.31; no.44, June 1993, p.36; no.58, December 1996, p.31; no.59, March 1997, p.31; no. 62, Summer 1997, p.35

Post Office Directory, 1947, 1949

Sunday Times, 28 May 1961; 26 February 1978 (photo of Frank Lloyd)

West Australian, 1955 – 1997

Interview (Ina Bertrand): John Marsden (1997)

Informant: Chris Simmonds (2002)

Photos: 1 interior (renovated concession), colour, 1992 (Chris Simmonds)

1 exterior, colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

photos, 1954, b & w, Roy Mudge

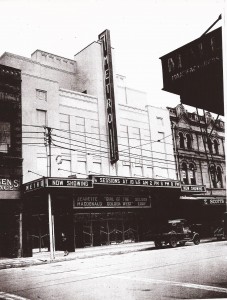

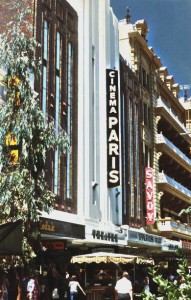

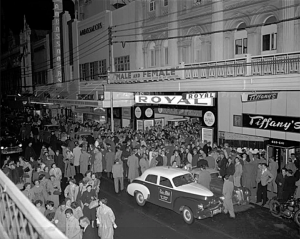

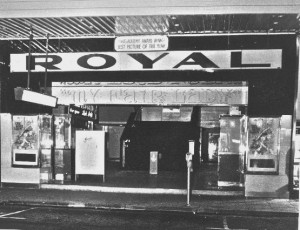

MAJESTIC/PLAZA/PARIS, 656 Hay St, Perth

MAJESTIC

P.A (Paddy) Connolly owned the Grand (later the Perth) Hotel, and there is an industry legend about his early involvement with films: Dennis Dease is said to have screened from the balcony of his hotel across Barrack St to a screen mounted on the wall of a shop opposite, till the police were called in to control the traffic jam which resulted, and Dease found himself in court on a charge of obstructing traffic (Weekend Magazine, 21 May 1966, pp.21-23).

I have been unable to confirm this story, but Connolly certainly became actively interested in the film business when a syndicate he headed built the Majestic Theatres, in Perth and Fremantle. They were in direct competition with the other cinemas opened during the First World War – the Palladiums (Perth and Fremantle), the Britannia, the Pavilion and the Grand. Like them, the Perth Majestic had a policy of cheap admissions and continuous programming. It opened on 21 December 1916, with accommodation for nearly one thousand people.

The auditorium will be furnished with the latest and most comfortable leather tip-up seats, and similar seats are provided in the gallery, but upholstered in Utrecht velvet. The proscenium is very fine, being specially moulded in fibrous plaster, with a striking ornamental mounting. The balcony front is also figured out in fibrous plaster, is most imposing, and forms a most artistic decoration. The whole of the ceilings are covered with Wunderlich metal, picked out in pleasing designs and charmingly painted. The vestibule is very lofty and commodious, and the lounge upstairs is roomy and bright and tastefully furnished. The operating cabin is built of brick and cement, and absolutely fireproof, and the very latest and improved biograph machines will, it is stated, be installed, reducing the risk to a minimum. Mirrors abound on the walls, vestibule and landings, and nickel-plated rails give the interior a very bright effect. The building is well-ventilated, and, in addition to a large number of oscillating fans, there are two very large sliding roofs, one over the auditorium and one over the gallery, which should make the building cool on the very hottest days and nights. The premises will be brilliantly lit with electric lights within and without. (West Australian, 9 December 1916)

On 27 July 1918 the cinema was taken over by J.C.Williamsons and in 1927, it became part of the Hoyts chain. Sound was installed in 1930 (it was the last of the city cinemas to join the trend), and in 1932 it became part of the General Theatres group when Hoyts and Union Theatres temporarily amalgamated.

In later years, a popular feature of the cinema were the working models constructed by R.W.(Dick) Burch for the foyer to advertise new programmes, bringing children in particular to gawp at the display.

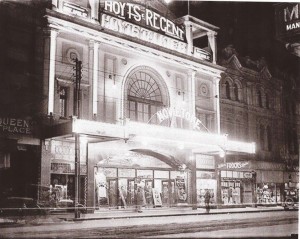

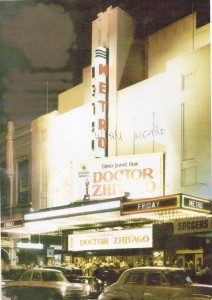

PLAZA/PARIS

Hoyts’ main city cinemas in the decade from their entry to the Perth scene in 1927 were the Majestic and the Regent. In 1937 the Majestic was demolished and a new, modern arcade was erected on the site, with shops on the street level and a cinema seating 1,313 – the Plaza – above. Shortly after, Hoyts relinquished the lease on the Regent, which became the Metro, so the Plaza took on the role of flagship for the company in Western Australia.

Architecture historian Ross Thorne describes it thus:

The facade to Hay St had a symbolic skyscraper effect. There were tall strips of windows; the centre third was taller than and projected from the remainder. Stepping from the centre of this central bay was the vertical sign which projected above the roof and curved back and down into the modern ziggurat roof form.

The auditorium was rather simple in fibrous plaster, striated lines and straight ceiling coves accentuated the long dimension of the room.

The slightly lower sections each side of the ceiling, as well as incorporating indirect lighting coves to wash light across upper ceiling levels and down the walls, probably boxed in the air conditioning ducts. (Ross Thorne, Cinemas of Australia via USA, p.274)

Further renovations, including the refurbishing of the interior and the installation of a Todd-AO sound system, were completed before the opening of South Pacific in 1960, which established a new long-run record for Perth of 45 weeks. The seating capacity of the theatre was reduced to less than one thousand in 1961.

On 17 August, 1965 the theatre closed, and re-opened two days later as the Paris. There were no major structural alterations this time, though later that year the entrance was resited in the Plaza Arcade. It was finally closed permanently in 1984, and the building was later converted into a disco.

In 1997 the cinema was derelict: the owners leased its entrances and exits for conversion into shops in the arcade, and access to the unused auditorium was only through a rear entrance on the laneway.

Sources: Building permits, Battye 1459, Folio 2

Max D. Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lews, Sussex, 1986, pp.83,89-90

Vyonne Geneve, ´William Leighton, architect’, Kino, no.25, September 1988, pp.7-15

Vyonne Geneve, ´The vulnerability of our Art Deco theatres’, Kino, no.28, June 1989, pp.6-8

Vyonne Geneve, Significant buildings of the 1930s in Western Australia, Vyonne Geneve, June 1994, National Trust of Australia (WA)/ National Estate Grants Programme, vol.1

Stage, Screen and Stars, West Australian, n.d. (1997?), pp.22, 41

Ross Thorne, Cinemas of Australia via USA, p.274

Everyone’s, 29 January 1930, p.18

Post Office Directory, 1917 – 1971

West Australian, 9 December 1916, 22 December 1916, 14 October 1960, 10 August 1961, 25 October 1965, 1916 – 1984

Interviews (Ina Bertrand & Bill Turner): Ray Cooper (1981)John Pye (1981)

Interviews (Ina Bertrand): Ken Booth (1981), Arthur Stiles (1985)

Photos: 1 exterior (Majestic), b&w, 1922, Battye 3187 11816P

2 exteriors (Majestic), b&w, 1936, West Australian, nos 1662/1753

1 interior, b&w, Ross Thorne, Cinemas of Australia via USA, p.274

1 exterior (Paris & Savoy), colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

1 exterior (Plaza), b&w, 1988, Kino, no.28, p.10 (Vyonne Geneve)

1 exterior (Plaza), b&w, undated, Wolanski collection ACTS, Kino no.72, Winter 2000, p.24

MAYFAIR/CAPRI, 721 Hay St, Perth

MAYFAIR

The Times Theatrette was the first small newsreel theatrette to be built in Perth, but it did not last very long: the Mayfair Theatrette was the second, opened on 25 June 1947 with only 380 seats. It was built by Joel Moss in the basement of Sheffield House, under Levinson’s, in Hay St.

The main programming of such theatrettes was the newsreel, and as the distributors refused to supply Moss with the major newsreels available at the time (Cinesound Review and Movietone News), he decided to produce a local newsreel, christened the Westralian News. One advantage of doing this was that both the existing newsreels came from Sydney and concentrated on news from the eastern states: a West Australian newsreel should have had more drawing appeal for the people of Perth. He formed a company (Southern Cross Newsreels Pty Ltd, later Southern Cross Films Pty Ltd), with himself and accountant John Macauley as directors, and Bill Duff as company secretary. Leith Goodall, who had worked as a stringer for Movietone, became chief cameraman, and arrangements were made for processing to be done by Herschell’s in Melbourne. The difficulties and cost of maintaining a regular schedule without local processing facilities eventually defeated the project, and when Cinesound Review was offered to the Mayfair Moss accepted and closed the Westralian News in October 1947.

The theatrette continued, quite successfully. Prices were cheap – in 1948, 1s plus 6d tax for adults, and 6d without tax for children. Sessions began at 10 a.m., and lasted approximately an hour, hence the popular label ´hour show’. There would usually be eleven each day, before the theatre closed around 10 p.m. or later, as most programmes were slightly longer than the advertised hour. The programme for 1 January 1949 could be considered typical: a topical short film on the Royal Christening, an overseas and an Australian gazette, a cartoon, a sporting film, a Fitzpatrick travel film, and a nature film entitled Mirror of Submarine Life.

Television, however, provided such programmes within the home, making newsreel theatrettes redundant. The Mayfair maintained its policy of continuous programming longer than its competitor, the Savoy, which had opened in 1955. When it finally succumbed, it followed the Savoy’s lead and ran six to eight sessions daily, of shorts and a feature in almost continuous programming, still appealing to the same audience – shoppers and others with a couple of hours to kill in the city.

After Moss’s death the cinema was managed by Mr Monahan, who married Joel Moss’s widow, Esme Moss: after Monahan’s death, Esme Monahan managed the cinema herself. The Mayfair closed 25 May 1968.

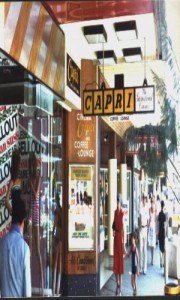

CAPRI

The venue re-opened, however, on 10 June 1968, as the Cinema Capri, now owned by Ace Theatres, but still managed by Esme Monahan:

Entrance to the theatre has been resited, cutting out what was previously a rather ‘tricky’ spot, and taking it close to the candy bar and coffee lounge, thus bringing these to the immediate attention of patrons.

The coffee lounge has telephones at every table, allowing patrons to place their orders without having to wait for service.

This section of the theatre is open from 10 a.m. until 11 p.m. to members of the general public who may not want to attend a screening on that particular occasion. (Film Weekly, 20 June 1968)

It was now programmed as a conventional city theatre, and continued with this policy till the late seventies, when Ace were feeling the effects of the cinema slump. They closed the Paris, but wanted to retain the Capri as an outlet for some of the films they were distributing, so made an arrangement with Peter Thomson, then managing the venue, to take over the lease but to continue to get his film supply through Ace.