Quicklinks

| Esperance | Exmouth | Finucane Island |

| Floreat Park | Forrestfield | Fremantle |

ESPERANCE

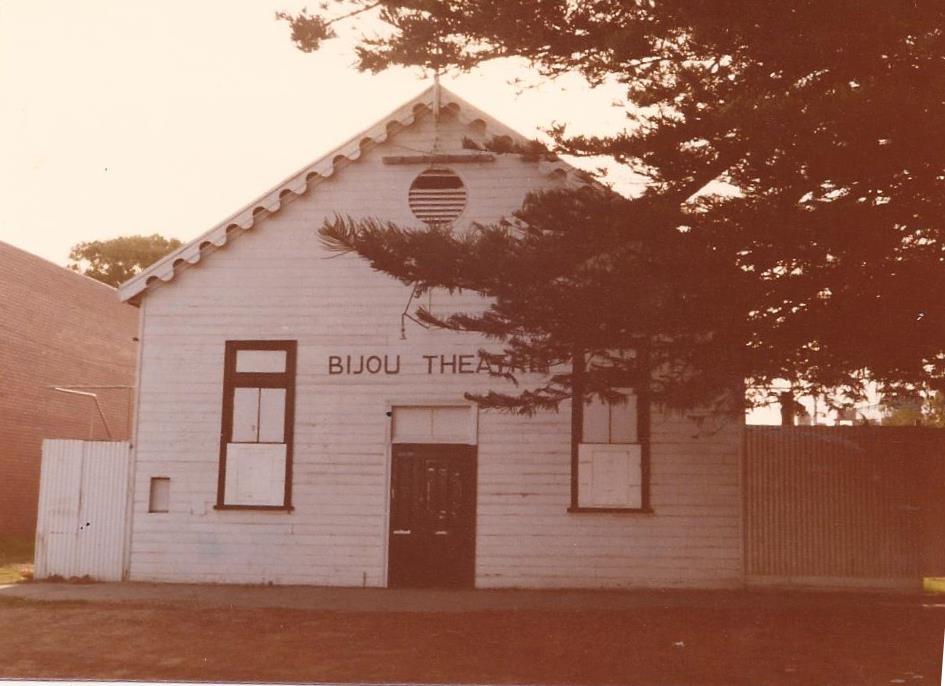

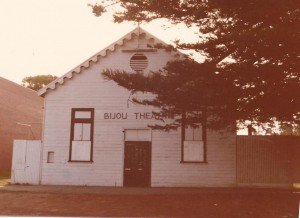

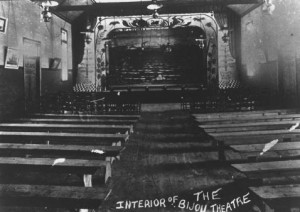

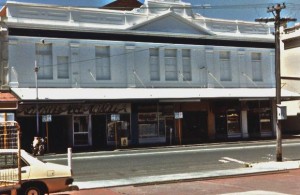

BIJOU/ R.A.O.B. HALL ,Dempster St, Esperance

The Bijou Theatre was built in August 1896 (over a period of only 31 days) on the west side of Dempster St, near William St. It was officially opened on 5 September 1896. The Esperance Municipal Heritage Inventory describes it like this:

The size of the original building was 93ft x 32ft, height 22ft, auditorium 55ft x 32ft with stage 17ft x 30ft. The floor was pine. Two backdrop scenes were painted by H Gough, one of West Beach and the “Grace Darling” entering the harbour and the other scene of a drawing room. Patrons were seated on wooden stools and chairs. Illumination was by six large kerosene lamps.

The building had been owned originally by the Adelaide and Esperance Land Company and was managed for them by E.J.McCarthy. In 1947 it was purchased by the R.A.O.B.: in 1971 they sold it to Esperance Repertory and built the new grey brick meeting hall behind the Bijou.

The Bijou had a weatherboard facade, but was mainly built of corrugated iron over a timber frame. It was a multi-purpose community building, used occasionally for film screenings in the early days and more regularly (under various proprietors) from the thirties to the mid-sixties.

This was where ‘Ilham the Afghan’ conducted his occasional screenings of silent pictures in the twenties. He travelled with a horse-drawn caravan, carrying a portable power plant, just powerful enough to run the carbon arc but not to also run a projector. So he hand-cranked the projector – Philip Hancock suggests he was perhaps ‘an early candidate for R.S.I.’ (letter to Neville Mulgat). Because his visits were irregular, he needed to be able to let the town know when a screening was to take place: so he employed a custom common at the time, of a boy from the local school acting as ‘Town Crier’, walking round the streets ringing the bell and calling out the slogan for the films.

Cran Smither reminisces:

All preparations completed the single cylinder engine outside was cranked up and Mr Ilham brought the two carbon rods together and with a bright flash and sizzle an intense white light was made. The projector was hand turned all night by Mr Ilham at a very steady speed. By turning too fast the image on the screen was speeded up and if too slow the nitrate film was set on fire so Mr Ilham had a pair of scissors very handy to snip the film and therefore save the top reel from catching fire.

At this stage of film screening the projector was in the middle of the hall and the audience, so the use of scissors was the only safety device known. When the film was cut or a break occurred it had to be re-threaded through various cogs and gates and it was local custom for all the kids to count the break out: ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, one, OUT!! as is done now on space launches. This custom was also applied to a love scene (kissing only those days). The kiss was counted down and OUT. So the silent flicks of our early lives were not always silent…

Round about Mr Ilham’s visit to Esperance the hunt for empty beer bottles became keen (half penny each), the bigger kids hunted rats because the local Road Board paid a bounty on ears and tail so the streets became neat and tidy, free of vermin with the resulting few pennies going towards “the flicks”.

In the thirties, Les Anderson moved from Boulder to Esperance and by 1940 he was the owner of the Bijou. He screened films only once a week in winter and kept his income up by opening the hall for roller skating, but in summer he screened to good houses three nights a week. He also operated the power station, which meant he had to rush off at interval every night to regulate the power supply, while his wife Molly was showing advertising slides. Anderson sold out to Jack Scholey in 1946, who operated the business as Esperance Talkies, till he too sold it in the late forties to E. McFetridge, who in turn sold in the early fifties to Mick Lalor. From the late fifties till it closed in the mid-sixties it was operated by Esperance Theatres. No-one can remember any outdoor screenings in conjunction with the Bijou – perhaps it was just too cold in Esperance?

Brian (Bunny) Dunn went to the Bijou in 1937, when his uncle Reddie McCudden was operator. At that time they had two projectors and screened on Saturday night only, with the projectors on the balcony and the screen on the stage. When Mick Lalor owned the projectors, people would book for the pictures at Lalor’s shop. Patrons would come down from Kalgoorlie to the Bijou at Christmas, and Lalor would pack them in on extra deckchairs – with the ever-present danger of canvas tearing or frames giving way! Deckchairs were used in the hall because they were simple to move in when a screening was on, or out when the hall was needed for something else (such as badminton). After Lalor opened his drive-in, regular film screenings at the Bijou ceased.

The slide projector and slides from the Bijou are currently housed in the Esperance Museum. The Municipal Heritage Inventory describes the theatre today like this:

Today the Bijou retains the original facade but it now has raked seating, consisting of 160 padded fold up seats. A rear balcony accommodates stage lighting and sound operations. A bar/kiosk has been built inside the small entrance foyer. Steps either side lead up to the auditorium.

Sources: Film Weekly Directory 1940/41 – 1964/5

Shire of Esperance, Draft Municipal Heritage Inventory, place no.3

Max Bell, ´Esperance Bijou’, Kino, no.29, September 1989, p.17

Max Bell, Perth – a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes Sussex, 1986, p.101

R.C.Bridges, Footprints in the sand, self-published, n.d.

Informants: Brian (Bunny) Dunn (Esperance, 17 August 1997); Elaine Siemer (Esperance, 17 August 1997)

Letter, Philip Hancock to Neville Mulgat, November 1995

Letter, Peter & Cran Smither to Neville Mulgat, 23 January 1996

Notes of interview (Neville Mulgat): Molly Anderson (1996)

Phil Blake, http://members.westnet.com.au/dakota/INTRO and bijou

Photos: 1 exterior, b&w, n.d., Shire of Esperance, Draft Municipal Heritage Inventory, place no.3

1 exterior, b&w, 1988, Kino, no.29, p.17 (Max Bell)

1 exterior, b&w, 1916, Battye 26711P (reproduced http://members.westnet.com.au/dakota/bijou.htm)

1 interior, b&w, 1897, Esperance Museum (reproduced http://members.westnet.com.au/dakota/bijou.htm)

1 exterior, colour, 1997 (Graeme Bertrand)

1 exterior, Max Bell , 1980’s

CIVIC CENTRE, Council Place, Esperance

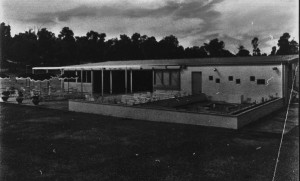

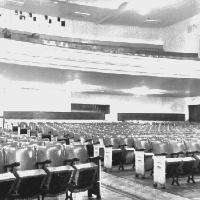

The large Civic Centre, including a hall, was built in Council Place, off Jane St, and opened in 1981. The Shire of Esperance brochure describes the venue in glowing terms: the setting among native plants and with ample parking space, the driveway with covered entry to the building, the auditorium with raked seating that can be converted to a flat surface by retracting the tiers on which the seats stand, the spacious stage with professional quality lighting and sound capacity, and the reception centre for smaller functions.

From 1981 it was occasionally booked by travelling film shows, using portable 16mm equipment. Then Christopher Baldwin and David Hayter initiated more regular commercial 35mm screenings there: with assistance from an experienced operator in Perth, they bought a second-hand 35mm projector and a screen. In 1995, David Hayter left the cinema, and Chris Baldwin brought in Phil Blake as weekend projectionist. Dolby Surround Sound wsa introduced in 1997, installed by Ron Tutt from Perth.

Because the venue was owned by the Shire, and no-one could have a monopoly on civic facilities, they were only able to book one month ahead, but occasionally, if they wished to book a blockbuster and the distributor required more than one month’s notice, that requirement was waived. In 1997, they did not screen every week – sometimes there were other events that booked the venue on a weekend. But when it was available, they screened on Friday and Saturday, 6 and 8 p.m. each day, with extra screenings (maybe 2 and 4 p.m. on Saturday) when they had a particularly popular film. They advertised in the Esperance Advertiser on a Thursday, and put up posters in the town.

Neville Mulgat in the Shire Office considered that the screenings were a boon to the town: they were popular with the young people, and rent to the Shire kept the Civic Centre viable, allowing it to make a profit in 1996. Popcorn made a mess, and the young patrons were sometimes very noisy, but that was a small price to pay for a valuable social activity. Regular screenings ceased in the Civic Centre when the new cinema complex opened in 2002.

Sources: Shire of Esperance, Draft Municipal Heritage Inventory, place no.8

Shire of Esperance, Esperance Civic Centre (brochure)

Max Bell, Kino no.21, September 1987, p.22

Phil Blake, http://members.westnet.com.au/dakota/ESPERANCE.htm

Informant: Neville Mulgat (Esperance 1997)

Photos: 1 exterior, b&w, n.d., Shire of Esperance, Draft Municipal Heritage Inventory, place no.8

exteriors and interiors, b&w, n.d., Shire of Esperance, Esperance Civic Centre (brochure)

1 exterior, 3 interiors, colour, n.d., http://members.westnet.com.au/dakota/ESPERANCE.htm (Phil Blake)

ESPERANCE DRIVE-IN, Sinclair St, Esperance

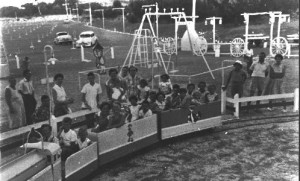

Mick Lalor had had the land for a drive-in for some time but had not proceeded with the building. The locals began to lose faith that he would ever build, so they approached Perth businessman Alan Larkin. A syndicate was formed, including Larkin and Goldfields Pictures as well as several Esperance businessmen. The company began construction, but so did Mr Lalor, and his Pink Lake Drive-in was already open when the Esperance Drive-in opened at the end of January 1966 in Sinclair St, on the corner of Fisheries Rd. At first it had places for 355 cars on seven acres, but the site was ten acres, allowing room for later expansion. The locally-made screen was 70ft by 34ft, and a playground and planting campaign were planned. W. Churchill moved from Norseman as manager.

It closed in the early eighties, re-opened over the summer of 1985 for three nights a week, but closed again the following year, permanently this time.

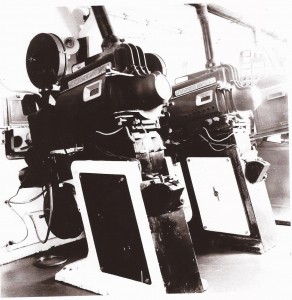

The Esperance Museum now holds one of the Gaumont Kalee Model 21 projectors and the Carbon arc slide projector in use at the Esperance Drive-in from 1967 to 1986.

Sources: Film Weekly Directory 1965/6 – 1971

Public Health Department, building permit, Battye 1459

Max Bell, Perth, a cinema history, The Book Guild Ltd, Lewes, Sussex ,1986, p.135

Max Bell, Kino, September 1985, no.13, p.14

Phil Blake, http://members.westnet.com.au/dakota/ESPERANCE.htm

Esperance Advertiser, 28 January 1966, p.6

Interviews (Ina Bertrand): Alan Larkin (1985), Ron Elsegood (1985)

Photos: 3 exteriors, colour, n.d., http://members.westnet.com.au/dakota/ESPERANCE.htm

(Phil Blake)

3 exterior ,sepia, Max Bell , 1980’s

FENWICK 3 CINEMAS, Esperance

Phil Blake describes how this 3-cinema complex was ‘built by a group of local residents along with two Victorian Cinema owners. The site on which the complex was built has historic importance being the site of the local legendary doctor John Fenwick who served the town for many years’. It opened 7 December 2002.

Sources: Phil Blake, http://westnet.com.au/dakota/PINKLAKE.htm

Kino, no.83, Autumn 2003, p.43

Photos: 1 exterior, 4 interiors, colour, http://members.westnet.com.au/dakota/ESPERANCE.htm (Phil Blake)

HANCOCK’S HALL, Andrew St, Esperance

Philip Hancock reminisces:

My father Cecil ‘Pop’ Hancock operated a picture theatre in ‘Hancock’s Hall’, Andrew Street from about 1926, so far as I can recall…

The theatre was a reconstruction of a shed which had previously served as a garage cum barn which became a dance hall and picture theatre. In earlier times the front of this place bore sign-painted evidence of the diverse and multiple skills of one, George Hearne, later to become store owner, funeral conductor and story teller. As a lad I calculated he was some 4 to 500 years old and had travelled adventurously and extensively throughout the then known world…

The hall seating consisted of a number of bentwood plus other chairs from the early Esperance Hotel, later delicensed. The front seating consisted of forms made up from the original shed flooring. The planks were about 15cm. wide and the forms when made up were appx. 20 cm. wide and 2½ m. in length.

The projection room was an asbestos construction. The Arc-lamp illuminated projection machine was driven and powered by a five horse power, petrol fed, Gardner upright single cylinder engine, with a long-belt coupled generator. The engine was water-cooled. Neither the dynamo nor the engine were satisfactorily bedded, being mounted on relatively light timber frames restrained by bags of sand against excessive vibration. The floor of the area was packed sand. Engine start was achieved by pulling on the belt to turn the motor, a dirty and somewhat hazardous arrangement. Under these ´Heath-Robinson’ conditions with leaking fuel, flooded engine, loose timing rods, poor insulation and with ´Pop’ dropping lighted papers into the plug hole in vain endeavours, the re-starting of the power supply would outperform any pantomime one could imagine. Sometimes patrons attending a showing on Saturday night would be issued passes to return on Monday evening and eventually complete the film Tuesday.

The exit door near the front stalls enabled access to such toilet facilities which, for want of suitable description, hardly existed. This door also enabled the many frantic trips to keep the plant operating. Another useful purpose was to allow ingress of ´Pop’s’ many aboriginal acquaintances. The usual idea was for the door to be opened after lights out so that when lights came on the scene was a bit different from before. Fleas were not at all uncommon.

The films of course were silent, in black and white. They arrived by rail Friday night, were wound joined and spooled by the operator big brother, Cecil. After display films were repaired, rewound and railed out Wednesday nights. From memory the hire cost per programme totalled in the vicinity (in today’s currency) of four to ten dollars. Except for the Christmas and Easter holiday periods, return from patronage was about the same. Admittance was, including 2 cents tax, 15 cents. The only justification for the display, given by ´Pop’ was that it brought people up to the shopping area, and gave a bit of life to the town.

The projector was operated by big brother Cecil who stood by the open door. It was his part to join the arc-light and see the film did not jam, if it did he was obliged to protect the frame thru which the film passed to prevent the flammable material bursting into flame from the heat intensity. He also changed to big reels after each two part section was completed. My own job was situated underneath the machine winding the expired film onto matching big reels, then quickly placing the reel of film into the steel fire proof box provided. There was an obvious incentive in performing the requirements quickly and carefully, I was not nearly close enough to the door.

The musical accompaniment was provided by ´POP’ Cecil Hancock who was I am sure a gifted musician. He would faithfully follow the action or mood of the film throughout, excepting that portion immediately preceding interval, at which point sound would stop. The reason for this would become apparent when on interval, those thirsty patrons repairing to the nearby inn would find that jovial musician already breasting the bar. ´MUM’ Emily Hancock sat at the entrance door and was cashier.

The Esperance Echo (8 August 1929) carried an advertisement for The Talkies, one night only, with full supporting programme of silents, but gave no indication of who the exhibitor was or where the presentation would take place. The very favourable review the following week still did not provide these details, but both Philip Hancock and Cran Smithers remember it as being in Hancock’s Hall: Philip Hancock found the sound-on-disk synchronisation very inadequate!

‘Pop’ Hancock’s own screenings ceased after sound-on-film was successfully demonstrated in the town and it became obvious that he could not afford to acquire quality sound equipment. Hancock’s Hall became Mick Lalor’s hardware store in the fifties, but it was later demolished and in the nineties the BP Service Station stands on the site.

Sources: R.C.Bridges, Footprints in the sand, self-published, n.d.

Informant: Brian (Bunny) Dunn, Esperance, 17 August 1997

Letter, Philip Hancock to Neville Mulgat, November 1995

Letter, Peter & Cran Smither to Neville Mulgat, 23 January 1996

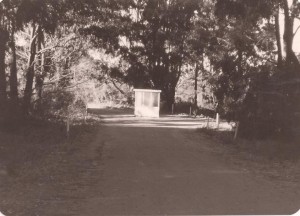

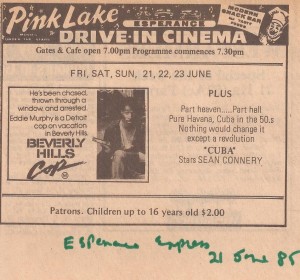

PINK LAKE DRIVE-IN, Freeman St, Esperance

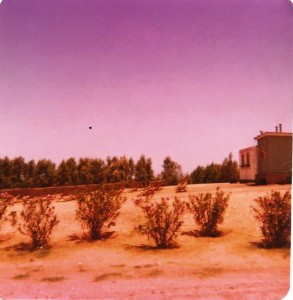

The Pink Lake Drive-in, with a capacity of 300 cars, was opened in Freeman St, beside the High School, on 15 December 1965. It was built for Mick Lalor, who had operated out of the Bijou, and continued to operate both venues for some time. It had a 90ft x 42ft screen, and buildings of the latest design:

All three buildings at the drive-in – ticket box, concessional building, and projection room are of American design.

The projection building is 20 feet square. It is built with Ravensthorpe stone.

It has a low flat-topped roof which enables people immediately behind it to see over the top.

The projection building is 300 feet from the screen.

The concession building, built of cream bricks, is about 65 feet long by 25 feet wide.

It contains a cafeteria and office.

The ticket box, a 19 feet by eight feet brick building, is well off the road to avoid congestion of cars outside the drive-in. (Esperance Advertiser, 17 December 1965, p.15)

Trees and shrubs were planted to beautify the venue, and a children’s playground was also planned, but the site was never sealed.

Phil Blake began his cinema career there as an assistant projectionist in 1977. On his web-site he describes the effect of video on audiences: declining patronage led to a brief closure in 1983, re-opening under a consortium that was also operating the Twin City Drive-in in Kalgoorlie, then final closure in 1985, after it had been operating in the summer months only. By 1986 the venue had been sold and the land was used for a private house, with some of the buildings converted.

Sources: Film Weekly Directory 1964/5 – 1971

Public Health Department, building permit, Battye 1459

Max Bell, Kino, September 1985, no.13, p.14

Max Bell, Perth, a cinema history, The Book Guild Ltd, Lewes, Sussex 1986, p.139-140

Phil Blake, http://westnet.com.au/dakota/PINKLAKE.htm

Esperance Advertiser, 17 December 1965, p.15

West Australian 1985 – 1986

Interview (Ina Bertrand): Alan Larkin (1985)

Interview (Colleen Pead): R.Yelland (1986)

Photos: 4 exteriors, colour, http://members.westnet.com.au/dakota/ESPERANCE.htm (Phil Blake)

1 exterior, Max Bell 1985

newspaper clipping, Max Bell

EXMOUTH

DRIVE-IN, Murat Rd, Exmouth

Jack Valli remembers the start of the drive-in like this:

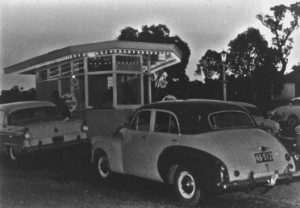

The then Civil Commissioner of Exmouth, Colonel J.P.K.Murdoch made a successful approach to Greater Union Theatres, and in late 1967 the Exmouth Drive-in Theatre opened for business in Murat road.

Colin Hatfield, who was running the small Panorama Drive-in at Roleystone in the late sixties, remembers that at that time television was starting to impact on drive-in audiences in the Perth suburban area. He says the town of Exmouth decided to investigate the possibility of a drive-in, and approached him for advice. He agreed to supply all the fittings and projection equipment, closed the Panorama in April 1967, transported the speakers and projection equipment to Exmouth and installed them on the prepared site. The screen was not ready, so the program he had brought with him could not be shown, and he returned to Perth.

Around Christmas 1967 Exmouth Shire Council approached Jim Woods with a request for his co-operation in the drive-in theatre venture. He agreed: the Council provided the venue and Woods provided the programming (coming up on the coastal ships from Perth, as they did to Derby, Carnarvon and Port Hedland). The venue was a combined gardens and drive-in, with provision for 104 cars, and 250 seated in the gardens. After television reduced the audience even here, Woods left (in around 1978-9) and the site was sold to a developer.

Jack Valli remembers the end of the drive-in like this:

As was the case around the nation, the Exmouth drive-in suffered a major blow when television came to the area, with the advent of the video striking a deathblow.

The property was sold to a developer in 1983.

For a while it was used as a storage yard for boats.

Sources: Film Weekly Directory 1968/9 – 1971

Public health Department, building permit, Battye 1459

Max Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, Sussex, 1986, p.135

Max Bell, Kino, no.15, March 1986, p.22

Jack Valli unpublished reminiscences

Interviews (Ina Bertrand): Colin Hatfield (1997), Alan Larkin (1985), N.J.Woods (1985)

HALL/NAVAL BASE THEATRE, Exmouth

Around 1965, at the peak of construction of the US Naval Communication Station at North West Cape, the work force exceeded two thousand. In the absence of any community facilities in the nearby town of Exmouth, this isolated community had no opportunities for social gatherings except in their own homes. Jack Valli (in unpublished reminiscences) remembers it like this:

Two supervisors, Australian Jack Valli and US civilian Harrison Waite, enlisted the support of the Resident Officer in Charge of Construction, Commander R.E.Dunnells, C.E.C, U.S.N., to introduce movies to the area.

Permission was received from the US Naval Motion Picture Exchange in Hawaii to have films shipped to the base on the weekly Military Airlift Command plane which serviced the base from Honolulu. An unused navy warehouse became a temporary theatre, and for the first time in Australia, pre-release Hollywood movies were shown on a nightly basis to an invited audience.

A single Bell and Howell 35mm projector was used, and the audiences quickly became used to periodic intervals as the reels were changed. The audience supplied their own seating, which ranged from empty fuel drums to reclining chairs.

Due to animosity from hundreds of uninvited workers, the management of second prime contractors Koppers-Clough made arrangements to provide their own theatre. Mr Jack Poon, principal of the catering contractors Poon Bros. set up a second theatre in the outdoor area adjacent to the camp, and movies were shown at both locations until the base was commissioned on 16th September 1967.

The N.M.P.X. movies were then taken over for use at the base theatre and entry was restricted to US citizens, to the chagrin of other nationalities. The then Civil Commissioner of Exmouth, Colonel J.P.K.Murdoch made a successful approach to Greater Union Theatres, and in late 1967 the Exmouth Drive-in Theatre opened for business in Murat road.

The commercial enterprise enjoyed considerable success over the years, with the “House Full” sign being a common sight. For several years the youth of Exmouth were also catered for due to the enterprise of the local Catholic priest Fr. Noel Tobin. His Saturday afternoon matinees at the Exmouth community hall were welcomed by the children and parents alike.

As was the case around the nation, the Exmouth drive-in suffered a major blow when television came to the area, with the advent of the video striking a deathblow.

The property was sold to a developer in 1983. Only the US Naval theatre remains as a film venue at North West Cape.

Sources: Jack Valli, Unpublished reminiscences

FINUCANE ISLAND

OPEN AIR CINEMA, Finucane Island

Jim Woods set up a venue here for the mining company, and when the company closed its operations Eddie Wheeler moved the projectors to the PCYC in Collie.

Sources: Interviews (Ina Bertrand): Eddie Wheeler (1997), Noel Wright & Diane Lockett (1997)

Photos: 2 exterior , Roy Mudge, 1978 and 1980

1 interior, Roy Mudge

FLOREAT PARK

SKYLINE DRIVE-IN THEATRE, Bold Park, Floreat Park

On 17 November 1955, less than a month after the Highway Drive-in introduced the drive-in concept to Perth, Hoyts opened the city’s second such venue – the Skyline. It was designed by Hobbs, Winning and Leighton, and was built on public land inside Bold Park, leased by Hoyts from the Perth City Council. Like the Highway, this offered a playground for the children and a snack bar and barbecues for the evening meal before the programme began, with the added attraction of a valet service for delivery of food direct to the car. It could accommodate 753 cars on opening, and this was later increased to 790. In July 1959, the lease was taken over by City Theatres, and the cinema became the first of their chain of drive-ins. The lease was not renewed on expiry in April 1986, but the cinema had a short reprieve while it was used as a viewing point for Halley’s Comet. It was then left dark till demolished in 1988, and the City of Cambridge Shire Offices now occupy the site.

Sources: Film Weekly Directory, 1955/6 – 1971

Max Bell, Perth – a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, Sussex, pp.128-9

Kino, no.16, June 1986, p.23; no.24, June 1988, p.23; no.49, September 1994, p.25

West Australian, 1955 – 1985, 2 June 1966, 20 July 1966

Photos: 5 exteriors, b&w, 1950s (Arthur Stiles)

5 exteriors, b&w, 1970 (Roy Mudge)

1 exterior, colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

2 exteriors, b&w, 1986 Kino no.49, September 1994, p.25 (Max Bell)

FORRESTFIELD

PARKLINE DRIVE-IN THEATRE, Hale Rd, Forrestfield

The Parkline was built for City Theatres, at a cost of £60,000, and was opened on 20 February 1964. Like the Skyline, it was designed by Hobbs, Winning and Leighton. It had provision for 400 cars:

The Parkline is in a beautiful setting with a background of pine trees and orchards and with nurseries nearby.

A creek runs through the property.

The drive-in itself occupies 15 acres but it has been set in an area of 40 acres to protect its surroundings and outlook….

It has been built to serve the hills districts and the foothills, new areas which are growing rapidly….

The Parkline has its cafe, projector unit and ticket bureau all in salmon bricks.

The cafe has modern equipment, special cooking appliances and a cool room.

It will serve a varied menu from 6.30 p.m.

Car attendants and cafe assistants will be drawn largely from nearby districts…

A modern sit-in area is adjacent to the cafe. (Sunday Times, 16 February, 1964)

In 1988, Hoyts took over City Theatres and immediately closed all six drive-ins: the Parkline was then sold for $950,000. In 1997 the land was used for a housing estate and shops.

Sources:Film Weekly Directory 1963/4 – 1971

Public Health Department, building permit, Battye 1459

Max Bell, Perth – a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, Sussex, p.128

Vyonne Geneve, ´William Leighton, architect’, Kino, no.25, September 1988, pp.7 – 15

Kino, no.25, September 1988, p.23

Sunday Times, 16 February 1964

West Australian, 1965 – 1988

Photos: 3 exterior, Max Bell 1980’s

FREMANTLE

BEACON AND GARDENS, 91 Hampton Rd, Fremantle (Beaconsfield )

After successes at the North Fremantle Town Hall and the Swan Picture Theatre and Gardens in Palmyra, Swan Suburban Pictures (James McKerchar and J. Veryard) built a new theatre and gardens in Hampton Rd at a cost of nearly £5,000. Designed by Samuel Rosenthal, it opened 17 August 1937 with Small Turn. The building permit was for ‘a stadium type theatre seating approx. 800’, and the gardens seating 500 were beside the theatre. Alterations were made in 1958, but it still closed in 1961 and was converted into a supermarket for Stammers Foodstores, its cinema origins still visible in the facade. In 1993 it was put on the market, and eventually sold, but, despite rumours of demolition and redevelopment, the gutted building remained on the site and was renovated in 1996-7, with parts of the frontage used for a chemist shop and then a video store. In 1999 a rumour was circulating that it was to be re-opened as a live entertainment centre, but in 2000 that had changed to a health and community centre.

Sources: Max Bell, Perth – a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, Sussex, 1986, pp.20, 55

Vyonne Geneve, Significant buildings of the 1930s in Western Australia, Vyonne Geneve, June 1994, National Trust of Australia (WA)/ National Estate Grants Programme, vol.1

Public Works Department, Building approval 11 March 1937 (Battye Library 1459)

Kino, No.10, December 1984, p.10; no.45, September 1993, p.31; no.50, December 1994, p.35; no.53, September 1995, p.31; no.57, September 1996, p.31; no.62, Summer 1997, p.35; no.67, Autumn 1999, p.31; no.73, Spring 2000, p.35.

Max Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, 1986 pp.20, 55

Vyonne Geneve, ‘The vulnerability of our Art Deco theatres’, Kino, no.28, June 1989, p.6

Interview (Mark Turton): James McKerchar (1978)

Photos: 1 exterior, Kino, No.10, December 1984, p.10 (Max Bell); no.28, June 1989, p.10 (Byron Geneve); no.32, June 1990, p.19 (Byron Geneve)

1 exterior, colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

CINE 2, 6 Elders Place, Fremantle

Opened in 1983, this was one of two cinemas operated by Club Adult Cinemas (the other being in Barrack St, Perth), screening non-stop adult movies. It was still operating in 1997.

Sources: West Australian 1985, 1988

EAST FREMANTLE TOWN HALL, Canning Highway, Fremantle East

In 1899, Sir John Forrest laid the foundation stone for this building designed by architect J.F.Allen, and additions housing the Library and Mechanics Institute opened in 1902. Many different educational and entertainment programmes took place in the hall, occasionally including moving pictures, but it was never used as a regular film screening venue.

ESSEX CINEMAS 1 & 2/ LUNA ON SX, Essex St, Fremantle

Two big showrooms had been built in the car park behind the food hall in Essex St, Fremantle – with access from a laneway running between Essex and Norfolk Sts. Peter Thomson, then operating the Capri in Perth, took on the lease to these buildings, and remodelled the premises into the Essex twin cinemas, which opened in September 1987. The two separate buildings were joined by what is now the entrance and foyer, and the showrooms converted to cinemas, the whole costing £250,000. Seating was provided for 330 in Essex 1 and 192 in Essex 2, and they were very successful. This was Thomson’s first venture into Fremantle, and he went on to establish Coastal Cinemas, with a monopoly in Fremantle and Rockingham.

In 1994, Coastal Cinemas bought the premises outright and in 1997 plans were announced to demolish the two cinemas and build a four-plex on the site, but (after zoning problems) the Millenium cinemas were built instead and the Essex continued as a twin, operated by the Luna company (which had begun in Oxford St, Leederville). They were reported to have opened two new screens on the site in February 2004.

Sources: Kino no.21, September 1987, p.22; no.22, December 1987, p.22; no.59, March 1997 p.26; no.87, Autumn 2004, p.38

Interview (Margaret Howroyd): Peter Thomson (1994)

Interview (Ina Bertrand): Peter Thomson (1997)

West Australian 1988 – 1997

Photo: Kino no.22, December 1987 (Max Bell)

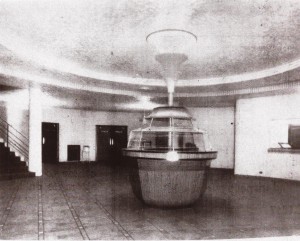

HOYTS FREMANTLE/ ORIANA, 177 High St, Fremantle

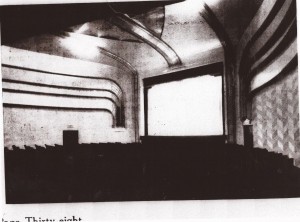

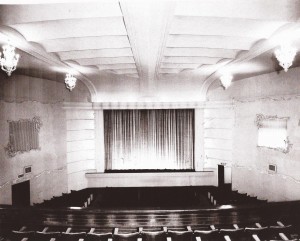

On the site of the old ‘Rose and Crown’ Hotel (and later also the Fremantle Grammar School), on the corner of High St and Queen St, Hoyts built a new theatre which they considered calling the ‘Crown’, but finally named simply Hoyts Fremantle. The architects were H. Vivian Taylor and Soilleux, in conjunction with Messrs. Oldham, Boas and Ednie-Brown. The Gala Opening (a screening of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Love on a Budget) was held on 4 August 1938:

Convenience for patrons has been the keynote in the construction of the new theatre, and the quaintly shaped ticket office allows easy access from all sides. The circular foyer is spacious and is designed to prevent any overcrowding. One moves naturally towards the various stalls entrances and cloakrooms and to the ample staircase leading to the dress circle and lounge. The various fittings have been carried out to harmonise with the decoration scheme, in which pastel shades of green predominate. Entrances and all floors of the theatre have been richly carpeted, and noteworthy features of the theatre include a crying room, in which mothers may take recalcitrant children without spoiling their own entertainment and without interfering with the pleasure of other patrons.

Special attention in the theatre has been paid to the acoustics and an unusual (and attractive) ‘ripple’ roof aids the sound equipment. Streamlined ‘fins’ extending from the proscenium to the circle railing also play their part in giving faithful sound recording. The interior decoration of the theatre is carried out in toning pastel shades and curtains, lighting and other fittings have been made to conform. The ‘floating screen’ is a new departure in screen entertainment which adds to the enjoyment of programmes. During intermissions patrons will enjoy the quiet luxury of the lounge, in which comfortable furniture harmonises with the decorative scheme. (West Australian, 5 August, 1938)

Among congratulations received on the opening night were messages from Samuel Goldwyn, Gary Cooper, Walt Disney and Shirley Temple, quite overshadowing the local dignitaries. When it opened, the theatre had provision for 1376 patrons, and was controlled by the Board of Hoyts, Fremantle Ltd, chaired by S. (Stan) W. Perry.

But not all patrons appreciated the luxurious surroundings. In September 1939, two teenagers were convicted of ‘rowdyism’ in the cinema, and fined for disrupting the screening. Mr W.F.Samson, then Secretary of Hoyts Fremantle, brought the charges, saying that:

These young people come armed with whistles and other contraptions to make hideous noises for the sole purpose of spoiling other people’s amusement. They come like lambs, and as soon as the lights go out they become jackals. (West Australian? Fremantle Gazette? 1 Sept. 1939)

The cinema continued to be known as Hoyts Fremantle till 1961, when it was taken over by City Theatres and renamed the Oriana. Renovations in 1967 reduced the seating capacity to approx.1000, and a new 70mm screen was installed as late as May 1968. But the cinema closed 4 December 1971, was demolished in March 1972, and the new building on the site used by Walsh’s Menswear.

Sources: Fremantle Library, cuttings collection

Max Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, 1986 pp.38-9

Max Bell, ‘Fremantle’s Theatre of Distinction’, Kino, no.65, Spring 1998, pp.30-31; no.66, Summer 1998, p.7.

Vyonne Geneve, ‘William Leighton, architect’, Kino no.25, September 1988, p.7.

Vyonne Geneve, ‘The theatres of the 30s in Western Australia’, Kino no.32, June 1990, p.18

Australasian Exhibitor, 16 May 1968 p.8

Film Weekly, 13 Aug. 1959, p.6

Film Weekly Directory, 1943/4 – 1971

Fremantle Advocate, 4 Aug. 1938

Post Office Directory, 1938/9 – 1949

West Australian, 5 Aug. 1938 p.4, 1938 – 1971

Interviews (Ina Bertrand): Ken Booth (1978), Chris Spivey (1978), Arthur Stiles (1978)

Interview (Ina Bertrand & Bill Turner): Jack Gynbn (1981)

Photos: 1 exterior (Oriana), b&w, 1969 (Roy Mudge)

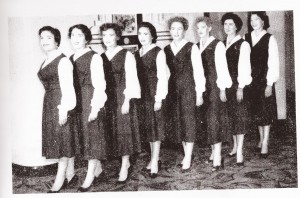

Interiors (Oriana auditorium, foyers, staff , bio box ) b&w, various dates (Roy Mudge)

1 exterior (Hoyts), colour n.d.

MAJESTIC, 115 (formerly 137) High St, Fremantle

The Connolly syndicate built and ran the Majestic theatres, opening first in Perth, then in Fremantle and Kalgoorlie. The Fremantle Majestic seated 1000, and was described as ‘a fine, imposing structure of generous proportions’ (West Australian, 9 December 1916), when it opened on 23 December 1916, after the official ceremony had been postponed for a day because of a power failure. In August 1918 the lease was taken over by J.C.W. Films, and in 1927 it became a Hoyts theatre, which it remained till it closed on 25 July 1938, in anticipation of the opening of Hoyts Fremantle. In fear that the Majestic lease would be taken over by another company who might operate in competition with their new theatre, Hoyts employees destroyed the fixtures and fittings on the day they vacated the premises, and opened the next day in the new theatre. The site was then occupied by a Homecrafts store, but the logo (MT) was still (at least to 1997) visible in the wrought iron of the balcony railings.

Sources:City of Fremantle, Rate Books

Fremantle Library, collection of cuttings

Public Works Department (Battye 1459)

Max Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, 1986 p.32

Hoyts Screen News, 1931 – 2

Post Office Directory, 1917 – 1938/9

West Australian, 2 Jan.1920 – 20 June 1920

Interview (Ina Bertrand): Ken Booth (1978)

Interview (Ina Bertrand & Bill Turner): Jack Gynn (1981)

Photos: 2 exteriors (different angles), colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

1 exterior ( Majestic) , b&w, date unknown, from the AMMPT archives

MILLENIUM CINEMAS, Essex Lane (off Collie St), Fremantle

The size of audiences at the Queensgate complex was noticeably affected by the opening of the Booragoon multiplex in the middle of 1997. The attraction was the megascreens, so fashionable in the mid-nineties, but the Queensgate complex could not be remodelled to include these. In anticipation of this problem, plans were developed in 1996 to convert the Essex St cinemas for such presentations, but Council approval was withheld because of the effect on the old mill site nearby. So Coastal Cinemas took an option on another site, on the southern side of Essex Lane, between Collie and Essex Sts.

Approval was obtained for a complex including four screens, of which two would be Megascreens. It was planned to open in June 1999, but building problems delayed opening till September 1999. In 21 December 2001, Hoyts took over this venue.

Sources: Interview (Ina Bertrand): Peter Thomson (1997)

Kino, no.63, Autumn 1998, p.34; no.66, Summer 1998, p.30; no.69, Spring 1999, p.35; no.70, Summer 1999, p.35; no.75, Autumn 2001, p.35.

West Australian 1999 – 2000

Photos: 2 exteriors, colour, 2001 (Graeme Bertrand)

ODDFELLOWS HALL/GAIETY/BIJOU, William St, Fremantle

The Oddfellows Hall in William St was described in 1889 as ‘a miserable place without convenience of any kind and for which extortionate terms were asked’ (Lt M.Rose, Inquirer and Commercial News 21 August 1889). It was renovated in 1890 and became known first as the Gaiety Theatre and then from 1898 to 1910 as the Bijou. The building was demolished around 1925 and the site was not again used as a theatre.

As the Oddfellows Hall, it was a multi-purpose building, and as the Gaiety or the Bijou usually a live theatre, but occasionally films were screened there. It is significant for this database because it was the site for a season of Harper’s Biograph Vaudeville Co, from 8 – 13 November 1897, that is, one of the earliest film screenings in Fremantle.

Sources: Fremantle City Council rate books 1867 – 1925

Inquirer and Commercial News, 21 August 1889

West Australian, 13 November 1897

Photos: 1 interior (Bijou Theatre), b&w, John Corrick?

OLYMPIA, Leake St (off 110 High St), Fremantle

The Olympia Roller Skating Rink on Lots 403-405 Leake St, was converted into a moving picture venue by the Star Amusement Co, and opened under the direction of C.Sudholz on 11 December 1909. The building was huge and cavernous, and in the conversion attempts were made to soften this effect:

The roof is being taken off the building in order to make the auditorium as cool as possible. Another feature is the new complete electric lighting plant which the company are installing to provide especially powerful light for their new machines. The Olympia Orchestral Band is rehearsing for the opening. (West Australian, 4 December 1909)

…the building has been structurally altered and the seating accommodation so arranged as to enable patrons to obtain a clear and uninterrupted view of the concert platform and screen. (West Australian, 15 January 1910)

The films were the same as those screened by the company at the Star Rink in Perth the previous week. Renovations further expanded the capacity of the building in March 1910, and for several years it presented films from August to the end of March, and skating for the rest of the year.In August 1913 an experiment was tried (advertised as ‘The very latest craze from London’, West Australian 2 Aug. 1913) of combining films and skating, but that does not seem to have lasted long. The advertisement for the ‘Grand Re-opening’ of Cecil’s Y.A.L.Pictures on Saturday 4 October 1913 was also the last advertisement for films in the venue. Later, the premises were used as a warehouse and offices.

During that part of the year when films were not shown at the rink, Olympia Pictures presented their programmes in the Victoria Hall.

Sources: Post Office Directory, 1913 – 1917

West Australian, 4 Dec. 1909 – 4 Oct. 1913

Photos: 1 exterior (Victoria Hall), colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

P.I.F.T./F.T.I., 92 Adelaide St, Fremantle

Perth Institute of Film and Television was formed in April 1971 when a group of people involved in film, television, education, the arts and the professions came together at a meeting held at the University of Western Australia to develop film and television as an art, an industry and as an educational tool.

Projects were subsequently initiated in West Australian Schools and at the University of Western Australia and work began on raising finance to develop the Film Institute in the Old Boys School in Fremantle as a centre. (Gateway, Spring, 1974)

In July 1974 PIFT moved into the school on a 20-year lease from Fremantle City Council, and converted the premises into offices and a 142-seat theatrette with the £400,000 raised for the purpose.

The building also housed the Community Education Centre, until the Princess May School renovations were completed, and the Centre moved in next door. After that, the Old Boys School building was shared with the W.A. Film Makers’ Co-operative, the W.A. branch of the Australian Council for Children’s Film and Television, and Community Radio. By March 1975, regular programmes of children’s films were being offered twice a week – after school on Fridays, and on Saturday afternoon. Adult seasons were at first provided only for members of the Co-op, but in October 1975 these were opened to the general public. The building became the W.A. home of the National Film Theatre of Australia, and later still of the Australian Film Institute. But as well as these institutional activities, the cinema operated as a commercial exhibitor of specialist programmes, particularly of local Western Australian productions, and other programmes unlikely to gain exposure through the normal commercial circuits.

During 1976 the Tavern opened on the site, independent of the cinema, but providing a congenial social focus for the complex.

On 14 October, 1977, Cinema 16 opened in a section of the downstairs hall, as ‘a new venue for the screening of innovative 16mm films’ (West Australian 14 Oct.1977), the opening programme being Pure S and Red Nightmare. Cinema 16 used canvas deck-chairs, of the type popular in the open air theatres of earlier days.

In 1984, the organisation was renamed the Film and Television Institute (FTI), and they later moved their films screenings to Perth, taking over the Entertainment Centre cinemas (the old Academy Cinemas) and renaming these the Lumiere.

Sources: Daily News, 5 Mar. 1975

Gateway, Spring 1974, vol.3, no.2, n.p.

West Australian, 27 Nov. 1975, p.24; 6 Apr. 1976, p.5; 17 Dec. 1976; 9 July 1977, p.28; 2 Nov. 1978, p.28,

Photos: 1 exterior, colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

1 interior (during renovations), b&w, Daily News 5 Mar. 1975

PALLADIUM 73 Market St, Fremantle

Fremantle Boys School Magazine, 15 Dec. 1914

Grand Gazette, nos.9-12 (3 – 24 Aug. 1918)

Post Office Directory, 1916 – 1925

West Australian, 2 Dec. 1914; 6 May 1976

Interview (Ina Bertrand): Chris Spivey (1978)

Interview (Mark Turton): James McKerchar (1978)

1 exterior (cinema entrance was where Reg Holland’s shop is in the picture), colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

PORT CINEMA/ PORT CINEASTE, 86 Adelaide St, Fremantle

On this site, a service station was demolished to build a £978,000 complex comprising offices, shops and undercover parking facilities. It was financed by the Fremantle City Council, from trust funds, so the Council were able to assure ratepayers that they would not have to carry any financial burden for the cinema within this complex. This cinema was named the Port, was leased to City Theatres, and opened on 17 December 1976:

In line with Council policy on new buildings, the building has been designed to blend with existing buildings, in this case the restored schools which are now PIFT and the Community Education Centre.

The Port Cinema is a plushly appointed, 400-seat theatre with the most modern and efficient projection equipment available.

The big first floor foyer overlooks the Princess May Park and a coffee shop on the ground floor actually spills into the park….

City Theatres plan to make the Port Cinema an important part of the life of Fremantle – and they have started with a policy of using new releases of films with a wide entertainment appeal.

The Fremantle City Council built the cinema after the constant demand by people in the city for a commercial cinema showing general films. (Daily News, 16 December 1976)

City Theatres was later taken over by a consortium, which sold all their theatre interests to Hoyts in 1988. In the rationalisation of Hoyts cinemas which followed, the lease of the Port was taken over by Peter Thomson of Coastal Cinemas, who also operated the Essex St cinemas and those in Queens Gate. It was then called the Port Cineaste, and new seating was installed in 1993. In 1997, after the FTI cinema moved to the Lumiere in Perth, it was the nearest thing Fremantle had to an arthouse cinema. However, when the Millenium Cinema opened in September 1999, the Cineaste was closed for conventional screenings, and used for previews and trade screenings only, until the lease expired in 2001, when the cinema went dark permanently.

Sources: Public Works Department, Building approval 29 Mar. 1976 (Battye Library 1459)

Max Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, 1986 p.39-40

Daily News, 16 Dec. 1976

Fremantle Gazette, (10 Dec. 1975?), 2 Dec. 1977

Kino, no.33, September 1990, p.23; no.43, March 1993, p.31; no.69, Spring 1999, p.35; no.78, Summer 2001, p.55

West Australian 1977 – 1997

Interview (Margaret Howroyd): Peter Thomson (1994)

Interview (Ina Bertrand): Peter Thomson (1997)

Photos: 25 interiors/exteriors, colour, 1981 (Roy Mudge)

1 exterior, colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

2 interior, colour, bio box, 1987, Roy Mudge

1 exterior, b&w, Max Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, 1986 p.39

PRINCESS, 32 Leake St, Fremantle

On the corner of Market St – next to the Terminus Hotel on the corner of Pakenham St, and opposite the Olympia skating rink – an old warehouse was demolished, to make way for West’s Princess theatre, opened on 21 December 1912, the first purpose-built hardtop in the suburban area. Seating 1850 persons, the new theatre was managed by T. M. (later Sir Thomas) Coombe till August 1914, when West’s opened another cinema at Subiaco and transferred their suburban operations there. Fullers vaudeville then operated the Princess for some time, till in March 1917 Coombe took over the theatre in his own right and brought it with him into the Union Theatres chain. Sound was introduced to the theatre in August 1929, and in 1935 it was taken over by the Grand Theatre Co, which employed William Leighton to design extensive renovations, including reducing the seating to 1540. This had been further reduced to 1200 by the time the theatre closed on 26 June 1969, a victim of the television boom. Peter Thomson describes how the cinema was showing four times a day Monday to Saturday and once on Sunday night before television: then screenings were reduced to twice a day and eventually closed altogether. The building was sold to a car repairer and gutted for use as a workshop, retaining the basic structure, including the balcony, and the entrance into Market St. In 1985 it was used as a market, and in 1989 by an icecream manufacturing company.

Sources: Fremantle City Council ratebooks 1910/11 – 1913/14

Max Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, 1986 p.41-2

Rodney I. Francis, ´The Coombe family of Perth’, Kino no.34, December 1990, pp.12-17

Rodney I.Francis, ‘Thomas Melrose Coombe: a pioneer from vaudeville to talkies in Western Australia’, Kino no.80, Winter 2002, pp.46-48

Vyonne Geneve, ‘William Leighton, architect’, Kino no.25, September 1988, p.7

Vyonne Geneve, Significant buildings of the 1930s in Western Australia, Vyonne Geneve, June 1994, National Trust of Australia (WA)/ National Estate Grants Programme, vol.1

Daily News, 27 July 1967; 2 July 1969

Everyone’s, 4 September 1929, p.32

Film Weekly Directory, 1943/4 – 1968/9

Grand Gazette, nos. 9-11 (3-17 Aug. 1918)

Post Office Directory, 1912 – 1949

West Australian, 10 Mar. 1961, 1912 – 1969

Interviews (Ina Bertrand): Ken Booth (1978), Lou Starr (1985), Arthur Stiles (1985)

Interview (Margaret Howroyd): Peter Thomson (1994)

Photos: 1 exterior, b&w, 1969 (Roy Mudge)

10 interior, b&w, 1969 (Roy Mudge)

1 b&w reproduction of cover of programme for gala re-opening 29 March 1941 (Arthur Stiles)

1 publicity stunt, b&w, Everyone’s 29 January 1930 p.18

Daily News took photos of Princess when it was opened as markets in 1983

Fremantle Library prints 964 – 967

1 exterior, b&w, Max Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, 1986 p.41

QUEENSGATE, William St, Fremantle

A sixplex was planned here, within the Queensgate shopping complex, built by Fremantle City Council. Negotiations for the lease of the cinema complex fell through, first with Hoyts in 1989, then with Greater Union, and construction was delayed by industrial disputes. By the time it finally opened, on 29 May 1990, the lease had been taken on by Peter Thomson’s Coastal Cinemas, which was already operating the Essex St twin.

This was the first suburban multiplex, and has had to be remodelled several times to keep up with the competition as more such complexes were built. For instance, in 1995 the sloping floors were replaced by stadium seating, and further remodelling is planned. But the structure cannot be remodelled to accommodate the megascreens of the later nineties, so the Millenium complex was built nearby for this kind of presentation.

Coastal Cinemas went on to acquire a monopoly of cinema in Fremantle and Rockingham, operating the business out of Queensgate, until Hoyts took over their venues on 21 December 2001.

Sources: Kino no.25, September 1988, p.23; no.27 March 1989, p.23; no.31, March 1990, p.23; no.33, September 1990, p.23; no.75, Autumn 2001, p.35.

West Australian 1990 – 2000

Interview (Margaret Howroyd): Peter Thomson (1994)

Interview (Ina Bertrand): Peter Thomson (1997)

RICHMOND AND GARDENS, 149 Canning Rd, Fremantle East

There is some suggestion that the Richmond started as a gardens on the north side of Canning Rd, opposite the Swan gardens. However, a building permit was issued for the Silas St corner on 21 May 1934, and records state that the theatre and gardens was completed on this site in December 1934 and operated by the Richmond Theatre and Gardens Co, which also operated the Swan\Mayfair (Palmyra). In the forties, the Richmond theatre and gardens each held approx 800, though in the latter years of its history this was reduced slightly to 750 each. It closed in 1961 and was demolished in 1979 to make way for a shopping complex.

In 1973 Jack Lee reminisced:

My father built the Richmond theatre and shopping centre in Silas St and a similar complex at the corner of Petra St and Canning Rd. The Richmond theatre and the open air section alongside it were later converted into a grocery supermarket. The Mayfair theatre is now a bingo centre and store. (Jack Lee, This is East Fremantle, Perth 1973, p.143)

Sources:Film Weekly Directory, 1943/4 – 1960/61

Post Office Directory, 1935/6 – 1949

Max Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, 1986 pp. 46,66

Jack Lee, This is East Fremantle, Perth 1973, p.143

SHARPE’S PENNY PICTURES, Holland St, Fremantle East

George Sharpe began a penny picture show in the backyard of his shop in January 1930. Attendance grew from 70 at the first show to as many as 250 for a Chaplin movie. The fire brigade forced the closure of the show as a fire hazard in 1933.

Ref: Sunday Times 21 March 1976

TOWN HALL/VIC´S PICTURES, High St, Fremantle

The Fremantle Town Hall was opened 22 June 1887. It was the location for the first screening of moving pictures in Fremantle, when Frank St Hill presented a programme on an Edison machine for one night only – Wednesday 16 December 1896. After that, touring companies presented occasional film programmes or short seasons there irregularly, and there were also occasional Sunday Rational Concerts presented, till West’s moved there from the King’s Theatre on 24 April 1909, to start the first permanent season. Irate citizens protested at their hall being leased in this fashion:

Money may be scarce with the civic fathers but that fact surely does not justify the ratepayers and many societies in Fremantle being deprived of the right to use the Town Hall on reasonable notice…

Apparently even the Mayor cannot have the Town Hall to convene a public meeting in. (letter to the editor, from Reuben Bailey, Baptist Manse, Fremantle, West Australian, 26 April 1909)

West’s continued to screen in the Town Hall, however, till the lease was taken over by Vic’s Pictures, a local company named after Victor Newton, one of the four partners in the business. They opened on 24 October 1910, and continued to screen there till 7 January 1919, by which time the company had expanded into the central business district of Perth and into other suburbs.

For many years, in the boom days of cinema in the district, when there were plenty of purpose-built venues available, the hall was used only occasionally for films. In the seventies, when there was no other venue available, it was revived by Peter Thomson and then taken over by local film-maker Daryl Binnings, who conducted mainly children’s matinees on Saturdays and special school holiday seasons. These screenings were sufficiently successful to persuade the Council that renovation to improve acoustics was justifiable, but the film screenings did not become permanent, and faded out in the eighties.

Sources: Fremantle Library, Collection of programmes and cuttings

Max Bell, ‘Fremantle Town Hall’, Kino no.51, March 1995, p.17

Max Bell, Perth: a cinema history, The Book Guild, Lewes, 1986 pp.26-28

John K.Ewers, The Western Gateway: a history of Fremantle, Fremantle City Council 1971

J.K.Hitchcock, The History of Fremantle: the front gate of Australia 1829-1929, Fremantle City Council n.d.

Post Office Directory, 1912 – 14, 1918

West Australian, 14 Dec. 1896 – 1 Mar. 1919; 22 Aug. 1973

Interviews (Ina Bertrand): Ken Booth (1978), Peter Thomson (1997)

Interview (Margaret Howroyd): Peter Thomson (1994)

Limelight Picture Show Tours, http//:www.abc.net.au/limelight/docs/tours

Photos: 1 exterior, colour, 1981

1 exterior, b&w, circa 1910 (from Fremantle Library collection)

1 exterior, b&w, J.K.Hitchcock, The History of Fremantle: the front gate of Australia 1829-1929, Fremantle City Council n.d. Hitchcock p.9

1 exterior, b&w, John K.Ewers, The Western Gateway: a history of Fremantle, Fremantle City Council 1971, opp. p.145

1 exterior, b&w, Kino no.51, March 1995, p.17

TOWN HALL/ARCADIA, 222 Queen Victoria Rd (Stirling Highway), Fremantle North

This imposing bluestone building holding around 400 patrons was constructed in 1902, and was used by touring film companies from at least 1906, when Bartlett’s Electric Biograph performed there. Permanent seasons appear to have started there during World War 1, under several different managements, none of which were particularly successful. James McKerchar had been employed by the BB Picture Co in Scotland (‘BB Pictures are Beautiful and Bright’), and by the railways in Western Australia before signing up for active service during World War 1. When he returned from the front in 1918 he spent his demobilisation pay to buy the plant and goodwill of the Town Hall picture show from a Mr Jones, and worked hard to build the business up. The patronage of the children was assured by screening serials, and of community groups by arranging fund-raising nights. As McKerchar only screened twice a day on Fridays and Saturdays, he was often able to obtain the services of Mrs Anderson on the piano, on her days off from the Palladium. Special competitions and entry prizes also helped, so that by the time he left in 1922 (for other venues in Palmyra and Fremantle East) the North Fremantle Town Hall venue was thriving.

There may have followed a period without a permanent management, until the Arcadia Pictures opened in September 1936, under the management of partners F. L. Martin, W. Sweeney and A. L. Cooper. It was operated by Martin and M.Corkhill (Corkell?) for some years, until Martin died in 1946. His (son/wife?) F. H. J. Martin continued briefly, then the business changed hands several times. Around 1951, Jimmy Barton was the operator when Peter Thomson worked as a tray-boy for a shop across the highway from the hall: working on commission, on Wednesday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday, he was able to earn about £1 a week – big money for an eleven year-old at that time!

The venue reverted in 1952 to the name North Fremantle Pictures, a name which remained till 1961 when film screenings ceased because the requirements of the Health Department for major renovations of the toilets could not be met. After a period of use by a local ballet group, the hall was taken over by the Fremantle Town Council (which had merged with North Fremantle Town Council) and sold to an antique company, which completely renovated the premises. In 1995 the hall was again put on the market.

Sources:The Heritage of Western Australia: the Illustrated Register of the National Estate, Macmillan 1989, pp.28-9

Max Bell, ‘North Fremantle Town Hall’, Kino no.50, December 1994 p.15; no.51, March 1995, p.31.

Letter from Mrs K. Melancon (daughter of Mr Martin), 16 April 1978, held in Fremantle Library

West Australian, 30 October 1975

Interview (Mark Turton): James McKerchar (1978)

Interview (Ina Bertrand): Peter Thomson (1997)

Photos:1 exterior, colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

1 exterior (foundation stone), colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

1 exterior, b&w, Kino no.50, December 1994 p.15 (Max Bell)

1 exterior, b&w, n.d. The Heritage of Western Australia: the Illustrated Register of the National Estate, Macmillan 1989, p.29

YE OLDE ENGLISHE FAYRE/PAVILION/DALKEITH OPERA HOUSE/KING�S/ TIVOLI/KING�S, 66 South Terrace, Fremantle

Ye Olde Englishe Fayre was a summer pleasure gardens in South Terrace, beside the Freemasons Hotel. Fremantle rate records list the Pavilion Theatre in 1899 – 1903 as on the same site, but it is not clear whether the Pavilion was within the Fayre or the two names were alternatives for the same enterprise. The Fayre was opened by Court and Butcher in October for the 1897 season, was apparently dark the next summer and was re-opened by Jones and Lawrence for the summers of 1899-1900 and 1900-1901. Jones and Lawrence introduced films to the site, as an occasional part of their vaudeville programmes in both summer seasons, but their programmes did not feature films as was done at the similarly-named site in Perth itself.

In 1904 the Dalkeith Opera House, later known as the King’s Theatre, was built on the site. It was designed by F.W.Burwell and built by Mr James Brownlie for entrepreneur James Gallop. At that time this was the most prestigious theatre in Fremantle. In 1909 The Official Guide to Western Australia (p.202) described it thus:

A handsome structure, built for the proprietor, Mr James Gallop, was opened on September 27, 1904. The theatre is situated in South Terrace, and adjoins the Freemason’s Hotel. The building, which is in the Renaissance style of architecture, has a neatly designed facade, and can accommodate about 1,200 persons, apart from the gallery. The building consists of one gallery only, viz. the dress circle, with accommodation for 300 persons; the auditorium is 68 ft. 6 ins. by 57 feet, with a height of 33 feet. The ceiling is furnished with ornamental ventilators, which can be rolled away; the sliding roof is also sufficient to leave an open space of about 10 feet square. The stage is 60 feet by 40 feet, with fly galleries at 26 feet and gridiron at 52 feet from the floor. The whole of the building is well provided in case of fire, there being 13 escape doors scattered throughout the theatre.

Later, architectural historian Warren Kerr (p.90) explained:

The main entry to the theatre was between shops at street level. This opened into a foyer through which the audience passed to the stalls in the auditorium. A staircase also led from the entry to supper rooms situated over the shops. From this on one side, the dress circle was accessible, while on the other, doors opened onto a balcony situated over the pavement, from which views of the ocean were possible. This promenade was 90 feet in length and lighted with �handsome’ gas lights.

It was, however, not without its critics, including Sydney-based entrepreneur Geo. Musgrove, who, while visiting the West damned the new theatre with faint praise, saying that it had three faults:

…the floor has been constructed without any slope at all, the second is that you are lighting it with gas, and the third is the horseshoe construction of the gallery. Never mind it is a really good theatre. (West Australian, 16 September 1904)

Almost at once, films were included in many of the programmes presented at the theatre, though it remained a predominantly live venue. Cozens Spencer, for a three-night films season in September 1905, advertised that he would instal:

a 220 volt 60 Ampere Dynamo, driven by 35 Horse power steam engine, which will supply a 3,000 Candle-power arc – a light that will enable Senora Spencer to reproduce and project the Company’s selection of the World’s ACME OF ANIMATED ART. (West Australian 21 September 1905)

Local Fremantle subjects were occasionally shown here, including film of the Perth versus East Fremantle football match on 29 September 1906. Leonard Davis introduced regular film screenings by various companies on Sunday evenings from 10 November 1906, the first such shows in Fremantle. These continued, with other screenings irregularly on weeknights, till West’s opened their permanent Fremantle season there on 31 October 1908. They shifted to the Town Hall in April 1909, but returned to the King’s in October 1910. In both sites, these ‘permanent’ seasons were occasionally interrupted for other uses of the premises, so the company must have been relieved when they took over the newly-constructed Princess in December 1912. After this, the Young Australia League conducted the regular screenings in the King’s theatre, but only on Saturday and Monday, while Davis continued to present the Sunday concerts. For a short time from April 1914 it was called the Tivoli, but soon reverted to the name ‘King’s’. The rash of purpose-built cinemas during and after World War 1 brought too much competition to the King’s: it returned to its original policy, and from 1919 presented only vaudeville till it was closed permanently in the late twenties.

In February 1921, the following news report appeared in the West Australian:

A PEANUT STRIKE

The latest body to be affected by industrial unrest is that of the boys employed to sell peanuts at the King’s Theatre, Fremantle. An altercation arose among the boys as to the method of working the theatre, and authority in the person of their employer descended upon them and “sacked” two of their number. A stop work meeting was held immediately, and the extreme element gaining control a strike was called. It was not long however before the familiar cry of “Peanuts, lollies, and chocolate” was heard ringing through the hall, and the extremists were informed that they “could have the strike all on their own.”

The building was converted for use as a panel beating shop. A plan by Sir Benjamin Fuller to reopen the theatre as a vaudeville venue after World War 2 fell through. In 1979 the building was converted into an ice skating rink, and in 1984 it was in use as an unlicensed disco. Another plan to renovate the building as a cinema in the late eighties also fell through, and in 1997 it was in use as shops and offices, though the facade was still impressive. After renovation, which earned a heritage award from Fremantle City Council, it became the Metropolis nightclub, which was the venue for a celebration of the centenary of the building, on 8 October 2004.

Sources: Fremantle City Council ratebooks 1898 – 1928

The Heritage of Western Australia: the Illustrated Register of the National Estate, Macmillan 1989, p.21

Max Bell, �Fremantle Opera House/ Kings Theate’, Kino no.59, March 1997, p.26

Louise Dumas, �Fremantle’s seaside opera house’, Fremantle Gazette, 26 October 1978, p.3

Jack Honniball, ‘Two theatres fit for a king’ Kino, no. 90, Summer 2004, pp.8-9

Warren Kerr, Architecture in Fremantle 1875 – 1915, the author, 1973, pp.89-92

Everyone’s, 20 March 1929, p.37

Mail, vol.1, no.164, 9 July 1904

Official Guide to Western Australia, Wigg & Sons, December 1909

Post Office Directory, 1899 – 1937/8

West Australian, 22 February 1904; 16 September 1904; 21 September 1905; 21 February 1920; 20 March 1920

Interview (Ina Bertrand): Ken Booth (1978)

Photos: 1 exterior, colour, 1981 (Bill Turner)

1 exterior (Dalkeith Opera House), The Heritage of Western Australia: the Illustrated Register of the National Estate, Macmillan 1989, p21

2 exteriors (sketch 2004, photo undated), Kino, no.90, Summer 2004, p.8