This talk was given at the AMMPT meeting on Wednesday 17th August, 2011 by Ian Stimson. This was a presentation on the the history of almost forgotten film gauges, of which 17.5 mm was one.

As I started out to research this subject I had not realised how long this film format had been in use. It started in 1890’s and used until recent times.

17.5 mm Formats

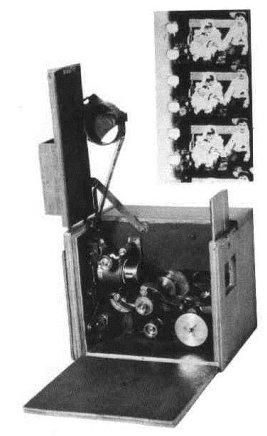

Birtac (17.5 mm) Format

In 1898 Birt Acres an English cameraman and inventor commenced slitting 35 mm film in half for his Birtac camera projector. Nitrate film of course, non flammable film base was yet to be developed at this stage. The camera used film of 17.5 mm with 2 holes on one side. This is the first device that uses small-format film that was made for domestic use.

Biokam (17.5 mm) Format

In 1898 in London, England, Alfred Wrench and Alfred Darling created another 17.5 mm with a central perforation. The camera, the Biocam, served as both camera and projector. The Warwick Trading Co. of London was the manufacturer. The Biokam also offered a still picture release, so that still pictures could be taken with the camera as well as cine films.

Hughes (17.5 mm) Format

In 1900 in London, W.C. Hughes created a camera similar to the Biocam, which he calls the “Petite”. It also served as both camera and projector. The 17.5 mm film also had a central perforation, although in a different form to the Biocam, it had smaller perforations.

Whilst across the channel other countries were trying out 17.5 mm using a centre frame perforation.

Ernemann Kino (17.5 mm) Format

In late 1902 the German Ernemann Kino cine camera was produced and this used the centrally perforated 17.5 mm film, this produced a picture size of 16 x 10 mm.

The Ernemann Kino I movie camera made Ernemann popular in Germany since it was the beginning of amateur movie making in that country. The Ernemann Kino II was manufactured in 1904. In 1926, Ernemann merged with three other camera makers Contessa-Nettel, Goerz and Ica to form the German company Zeiss Ikon, with an infusion of capital by Zeiss. Ernemann’s line of projectors continued to be named “Ernemann”, which set the standards for cinema movie projection in Germany.

Kretschmer (17.5 mm) Format

In Dresden, Kretschmer created a camera similar to the Kino that was made by Ernemann.

Ikonograph (17.5 mm) Format

In 1905, the Ikonograph Commercial Co. of Manhattan (New York) sold the projector “Ikonograph” which used a film of 17.5 mm. The projector was designed by Enoch J. Rector and was an improved model of the Ernemann.

Duoscope (17.5 mm) Format

In 1912 in London, the Duoscope Ltd. company introduced the Duoscope device, which served both as cine camera and projector. It used a film of 17.5 mm with two holes between adjacent main frame and frame.

Sinemat (17.5 mm) Format

In 1915, the company Sinemat American Motion Picture Machines presents a cinematic device that used 17.5 mm film with holes on one side. This device was used both as a camera and a projector.

Movette (17.5 mm) Format

In 1917 Movette Inc of Rochester New York launched their machine using a magazine loaded with 17.5 mm nitrate film. This was perforated with round holes on either side of each frame. It had 4 perforations per frame, 2 on each side.

This negative film was developed by Kodak and printed onto safety stock for projection. As time passes and Eastman introduces 16.0 mm size film in 1923, the experimental work had been started on this format by John Capstaff earlier in 1914.

Actograph (17.5 mm) Format

In 1918, the Wilart Instrument Co. of New Rochelle (New York), manufactures a camera to film 17.5 mm. The camera was called “Actograph.”

Bell and Howell (17.5 mm) Format

Bell and Howell had expanded into the amateur movie market in 1919 when the company began developing 17.5mm equipment. Before Eastman Kodak’s experiments with l6mm reversal film, following which they redesigned all the company’s 17.5mm equipment to use 16mm film.

Closes (17.5 mm) Format

In 1920 in Austria, a company manufactured a device for 17.5 mm cinematographic film. This film had two round holes adjacent area between frame and frame.

Coco (17.5 mm) Format

In 1920 in Germany, the home of Munich Linhof, made a 17.5 mm film device called the “Coco.”

Cinétype (17.5 mm) Format

In 1925 in Paris, a company sold the Mollie “Cinétip”, a cinematic device that mixed camera and projector. This device used a film of 17.5 mm with holes on one side.

Moving on to 1926, Pathé are back on the scene, this time with their own 17.5mm standard double sprocketed film, the same as Eastman’s 17.5 mm, perhaps launched as a competitor to Kodak. This was launched after their 9.5mm. It became popular for the amateur film maker.

The new Pathé 17.5 mm film was launched as the “Pathé Rural” double sprocketed with a perforation on each side, that used safety stock, producing a picture size of 9 x 12 mm. This was first revealed to the “Society Fancais de Photographie” on 10 February 1926.

Printed films were produced by printing them in pairs on specially perforated 35 mm safety stock, using the 35 mm masters in reduction printers.

The French, it seems, intended this format for use in the country districts cinemas on their Pathé circuit, the name they used was “Rural.”

But problems in 1927 with machine production, and finding film distribution rights too expensive, this slowed the business down. In the UK 17.5 mm was hardly advertised at all.

However in France, before WW2 there were no less than 4823 cinemas in the country screening in 17.5 mm format.

In 1932 sees the introduction of 17.5 mm sound on film, the projection equipment was very sophisticated, even though the outfit looked a little bulky. To accommodate the sound track in the film, the perforations were removed from one side.

Pathé chose to use the variable area RCA sound track over sound on disc recorded sound.

Pathé machines was called the Rural Sonora Optical Sound Projectors, and sold in England as the “REX.”

Each machine had a 750 watt lamp for projection, with separately powered exciter lamp to reproduce the sound.

The 17.5 mm format appears to have been a success until WW2 however when France was occupied by Germany. They found that 17,5 mm was non standard, at least to the Germans, and they, becoming occupying authorities decided to ban the film size.

However Pathé was allowed to circulate their currently in production programs, then all of the prints were order to be destroyed by the German occupiers.

Most of the Projectors were scrapped or converted to 16mm, some machines have survived along with film, it has been alleged that many machines and film was buried out of sight in gardens and back yards.

Hitler’s order banning 17.5 mm film size; this was proclaimed on 30th June 1941 loosely translated it said.

“ORDRE DE LA PROPAGANDA ABTEILUNG”.

It said all films in this format found in cinemas are to be returned to the distributors and it is now forbidden for distributors to deliver films in this format. The conversion of all 17.5 mm cinemas to 16mm, the only authorised format, was to be carried out as quickly as possible.

There the format might have died, but film producers and some news cameramen kept the format alive from 1940 into 1950’s.

The last foray into 17.5mm was done here in Australia by Stanley Kramer. He had specially modified Mitchell camera’s to take this gauge of film.

The film was ‘On The Beach’ which was based on the 1957 novel by author Nevil Shute. The movie was released in 1959 and features Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner, Fred Astaire and Anthony Perkins. Stanley Kramer won the 1960 BAFTA for best director. Ernest Gold won the 1960 Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture Score, which used Waltzing Matilda as the constant theme.

It was in fact 35mm film shot on a 17.5 mm gate, the film was then turned around, and the other half exposed. It was then printed up to 35 mm for cinema release.

I’m indebted to Bruce Dargie and Richard Ashton for this information as they were both extras in the crowd scenes.